Tag: Economic development

-

The Pete Meitzner era in Wichita

Wichita City Council Member Pete Meitzner is running for a position on the Sedgwick County Commission, touting his record of economic development. Here is the record.

-

From Pachyderm: Economic development incentives

A look at some of the large economic development programs in Wichita and Kansas.

-

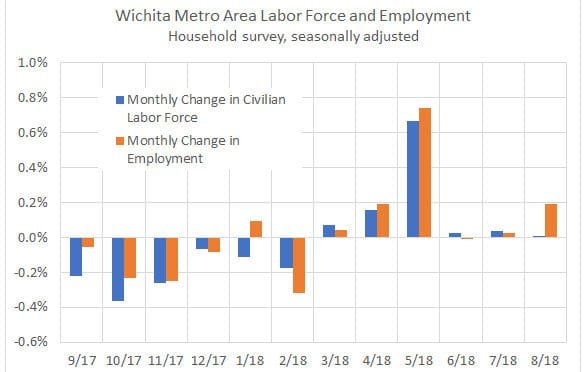

Wichita employment, August 2018

For the Wichita metropolitan area in August 2018, jobs are up, the unemployment rate is down, and the labor force is smaller, compared to the same month one year ago.

-

Kansas agriculture and the economy

What is the importance of agriculture to the Kansas economy?

-

Wichita economy shrinks, and a revision

The Wichita economy shrank in 2017, but revised statistics show growth in 2016.

-

More TIF spending in Wichita

The Wichita City Council will consider approval of a redevelopment plan in a tax increment financing (TIF) district.

-

Wichita Wingnuts settlement: There are questions

It may be very expensive for the City of Wichita to terminate its agreement with the Wichita Wingnuts baseball club, and there are questions.

-

Wichita, not that different

We have a lot of neat stuff in Wichita. Other cities do, too.

-

Sedgwick County jobs, first quarter 2018

For the first quarter of 2018, the number of jobs in Sedgwick County grew, but slower than the nation.

-

Business improvement district proposed in Wichita

The Douglas Design District proposes to transform from a voluntary business organization to a tax-funded branch of government (but doesn’t say so).

-

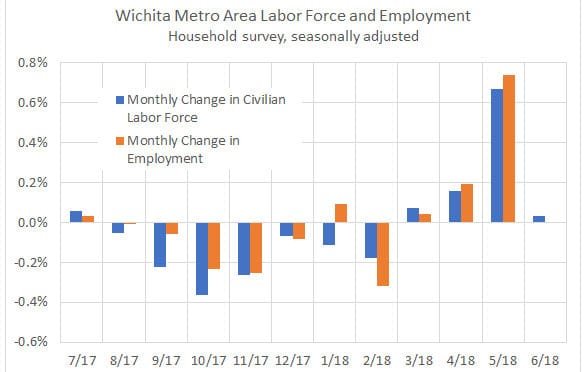

Wichita employment, June 2018

For the Wichita metropolitan area in June 2018, jobs are up, the unemployment rate is down, and the labor force is smaller, compared to the same month one year ago.

-

The Wichita Mayor on employment

On a televised call-in show, Wichita Mayor Jeff Longwell is proud of the performance of the city in growing jobs.