Resources on tax increment financing (TIF) districts.

Tax Increment Financing: A Tool for Local Economic Development. Richard F. Dye and David F. Merriman. Tax increment financing (TIF) is an alluring tool that allows municipalities to promote economic development by earmarking property tax revenue from increases in assessed values within a designated TIF district. Proponents point to evidence that assessed property value within TIF districts generally grows much faster than in the rest of the municipality and infer that TIF benefits the entire municipality. Our own empirical analysis, using data from Illinois, suggests to the contrary that the non-TIF areas of municipalities that use TIF grow no more rapidly, and perhaps more slowly, than similar municipalities that do not use TIF.

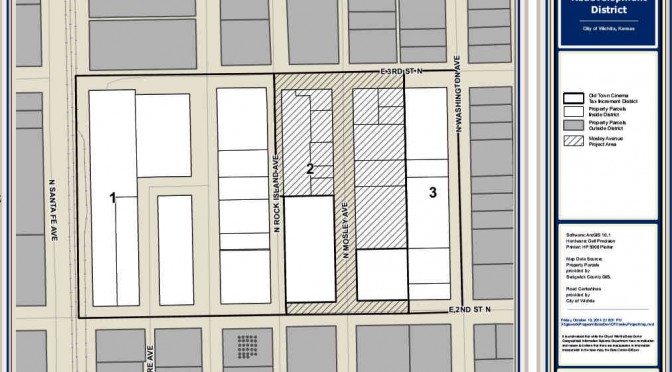

Wichita TIF projects: some background. Tax increment financing disrupts the usual flow of tax dollars, routing funds away from cash-strapped cities, counties, and schools back to the TIF-financed development. TIF creates distortions in the way cities develop, and researchers find that the use of TIF means lower economic growth.

The effects of tax increment financing on economic development. Richard F. Dye and David F. Merriman. Local governments attempt to influence business location decisions and economic development through use of the property tax. Tax increment financing (TIF) sequesters property tax revenues that result from growth in assessed valuation. The TIF revenues are to be used for economic development projects but may also be diverted for other purposes. We have constructed an extensive data set for the Chicago metropolitan area that includes information on property value growth before and after TIF adoption. In contrast to the conventional wisdom, we find evidence that cities that adopt TIF grow more slowly than those that do not. We test for and reject sample selection bias as an explanation of this finding. We argue that our empirical finding is plausible and present a theoretical argument explaining why TIF might reduce municipal growth.

Does Chicago’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Programme Pass the ‘But-for’ Test? Job Creation and Economic Development Impacts Using Time-series Data. T. William Lester looked at block-level data regarding employment growth and private real estate development. The abstract of the paper describes:

“This paper conducts a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of Chicago’s TIF program in creating economic opportunities and catalyzing real estate investments at the neighborhood scale. This paper uses a unique panel dataset at the block group level to analyze the impact of TIF designation and investments on employment change, business creation, and building permit activity. After controlling for potential selection bias in TIF assignment, this paper shows that TIF ultimately fails the ‘but-for’ test and shows no evidence of increasing tangible economic development benefits for local residents.” (emphasis added)

In the paper, the author clarifies:

“To clarify these findings, this analysis does not indicate that no building activity or job crea-tion occurred in TIFed block groups, or resulted from TIF projects. Rather, the level of these activities was no faster than similar areas of the city which did not receive TIF assistance. It is in this aspect of the research design that we are able to conclude that the development seen in and around Chicago’s TIF dis-tricts would have likely occurred without the TIF subsidy. In other words, on the whole, Chicago’s TIF program fails the ‘but-for’ test.

Later on, for emphasis:

“While the findings of this paper are clear and decisive, it is important to comment here on their exact extent and external validity, and to discuss the limitations of this analysis. First, the findings do not indicate that overall employment growth in the City of Chicago was negative or flat during this period. Nor does this research design enable us to claim that any given TIF-funded project did not end up creating jobs. Rather, we conclude that on-average, across the whole city, TIF was unsuccessful in jumpstarting economic development activity — relative to what would have likely occurred otherwise.” (emphasis in original)

The author notes that these conclusions are specific to Chicago’s use of TIF, but should “should serve as a cautionary tale.”

The Most Popular Tool: Tax Increment Financing and the Political Economy of Local Government. Richard Briffault, University of Chicago Law Review, Winter 2010. “Tax increment financing (TIF) is the most widely used local government program for financing economic development in the United States, but the proliferation of TIF is puzzling. TIF was originally created to support urban renewal programs and was narrowly focused on addressing urban blight, yet now it is used in areas that are plainly unblighted. TIF brings in no outside money and provides no new revenue-raising authority. There is little clear evidence that TIF has done much to help the municipalities that use it, and it is also a source of intergovernmental tension and a site of conflict over the scope of public aid to the private sector.

Yet, the expansion of TIF makes sense in light of the basic structure of American local government law. Studying TIF can illuminate central features of our local government system. TIF succeeds — in the sense of its widespread adoption and use — because it, like local government more generally, is highly decentralized; reflects and reinforces the fiscalization of development policy; plays off the fragmentation of local governments and the resulting interlocal struggle for investment; and fits well with the entrepreneurial spirit characteristic of contemporary local economic development policy. A better understanding of TIF contributes to a better understanding of the political economy of American local government.”

Wichita should reject Bowllagio TIF district. Wichita should reject the formation of a harmful tax increment financing (TIF) district.

Wichita TIF: Taxpayer-funded benefits to political players. It is now confirmed: In Wichita, tax increment financing (TIF) leads to taxpayer-funded waste that benefits those with political connections at city hall.

Tax increment financing (TIF) and economic growth. There is clear and consistent evidence that municipalities that adopt tax increment financing, or TIF, grow more slowly after adoption than those that do not.

Does tax increment financing (TIF) deliver on its promise of jobs? When looking at the entire picture, the effect on employment of tax increment financing, or TIF districts, used for retail development is negative.

Crony Capitalism and Social Engineering: The Case against Tax-Increment Financing. Randal O’Toole, Cato Institute. While cities often claim that TIF is “free money” because it represents the taxes collected from developments that might not have taken place without the subsidy, there is plenty of evidence that this is not true. First, several studies have found that the developments subsidized by TIF would have happened anyway in the same urban area, though not necessarily the same location. Second, new developments impose costs on schools, fire departments, and other urban services, so other taxpayers must either pay more to cover those costs or accept a lower level of services as services are spread to developments that are not paying for them. Moreover, rather than promoting economic development, many if not most TIF subsidies are used for entirely different purposes. First, many states give cities enormous discretion for how they use TIF funds, turning TIF into a way for cities to capture taxes that would otherwise go to rival tax entities such as school or library districts. Second, no matter how well-intentioned, city officials will always be tempted to use TIF as a vehicle for crony capitalism, providing subsidies to developers who in turn provide campaign funds to politicians.

TIF is not Free Money. Randal O’Toole. Originally created with good intentions, tax-increment financing (TIF) has become a way for city officials to enhance their power by taking money from schools and other essential urban services and giving it to politically connected developers. It is also often used to promote the social engineering goals of urban planners. … Legislators should recognize that TIF no longer has a reason to exist, and it didn’t even work when it did. They should repeal the laws allowing cities to use TIF and encourage cities to instead rely on developers who build things that people want, not things that planners think they should have.

Does Tax Increment Financing Deliver on Its Promise of Jobs? The Impact of Tax Increment Financing on Municipal Employment Growth. Paul F. Byrne. Increasingly, municipal leaders justify their use of tax increment financing (TIF) by touting its role in improving municipal employment. However, empirical studies on TIF have primarily examined TIF’s impact on property values, ignoring the claim that serves as the primary justification for its use. This article addresses the claim by examining the impact of TIF adoption on municipal employment growth in Illinois, looking for both general impact and impact specific to the type of development supported. Results find no general impact of TIF use on employment. However, findings suggest that TIF districts supporting industrial development may have a positive effect on municipal employment, whereas TIF districts supporting retail development have a negative effect on municipal employment. These results are consistent with industrial TIF districts capturing employment that would have otherwise occurred outside of the adopting municipality and retail TIF districts shifting employment within the municipality to more labor-efficient retailers within the TIF district.

Tax Increment Financing and Missouri: An Overview Of How TIF Impacts Local Jurisdictions. Paul F. Byrne. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) has become a common economic development tool throughout the United States. TIF takes the new taxes that a development generates and directs a portion of them to repay the costs of the project itself. … Supporters of TIF argue that it is a necessary tool for redevelopment in older communities. Detractors contend that it is used to simply subsidize development, and that variances in tax systems allow some governments to implement and benefit from TIF even if its use harms other levels of government. This study provides an overview of the history and basic structure of TIF. It then analyzes the basic tax components of a TIF plan and compares how various aspects, such as tax capture and tax competition, play out in the standard system of TIF. The study then reviews the economic literature on TIF, and ends with a direct application of how TIF operates within Missouri.

The Right Tool for the Job? An analysis of Tax Increment Financing. Heartland Institute. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is an economic development tool that uses the expected growth (or increment) in property tax revenues from a designated geographic area of a municipality to finance bonds used to pay for goods and services calculated to spur growth in the TIF district. The analysis performed for this study found TIF does not tend to produce a net increase in economic activity; favors large businesses over small businesses; often excludes local businesses and residents from the planning process; and operates in a manner that contradicts conventional notions of justice and fairness. We recommend seeking alternatives to TIF and reforms to TIF that make the process more democratic and the distribution of benefits more fair to residents of TIF districts.

Giving Away the Store to Get a Store. Daniel McGraw, Reason. Largely because it promises something for nothing — an economic stimulus in exchange for tax revenue that otherwise would not materialize — this tool is becoming increasingly popular across the country. Originally used to help revive blighted or depressed areas, TIFs now appear in affluent neighborhoods, subsidizing high-end housing developments, big-box retailers, and shopping malls. And since most cities are using TIFs, businesses such as Cabela’s can play them off against each other to boost the handouts they receive simply to operate profit-making enterprises. … At a time when local governments’ efforts to foster development, from direct subsidies to the use of eminent domain to seize property for private development, are already out of control, TIFs only add to the problem: Although politicians portray TIFs as a great way to boost the local economy, there are hidden costs they don’t want taxpayers to know about. Cities generally assume they are not really giving anything up because the forgone tax revenue would not have been available in the absence of the development generated by the TIF. That assumption is often wrong.

Do Tax Increment Finance Districts in Iowa Spur Regional Economic and Demographic Growth? David Swenson and Liesl Eathington. We found virtually no statistically meaningful economic, fiscal, and social correlates with this practice in our assessment; consequently, the evidence that we analyzed suggests that net positions are not being enhanced — that the overall expected benefits do not exceed the public’s costs.

No More Secret Candy Store: A Grassroots Guide to Investigating Development Subsidies. From Good Jobs First, a comprehensive guide to researching state and local subsidies, economic development agencies, and companies.