Tag: Greater Wichita Partnership

-

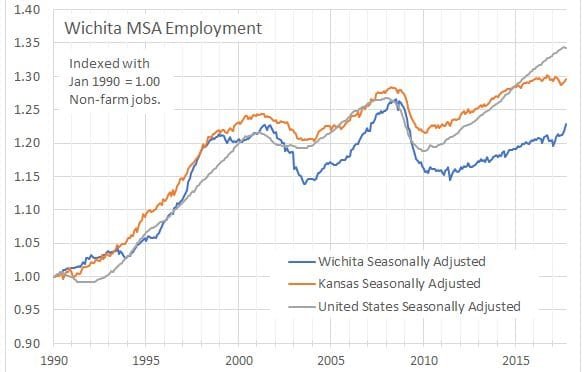

Wichita employment down, year-over-year

At a time Wichita leaders promote forward momentum in the Wichita economy, year-over-year employment has fallen.

-

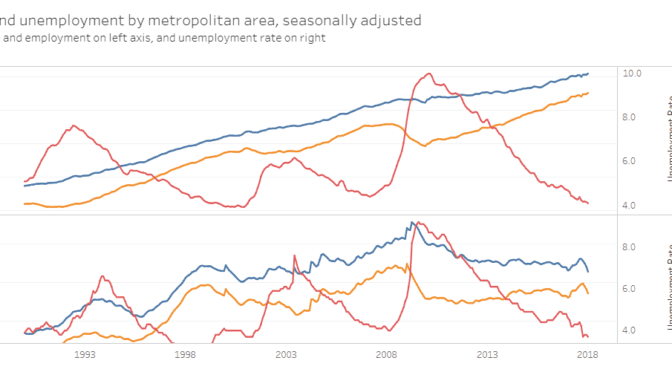

Employment in metropolitan areas

An interactive visualization of labor force, employment, and unemployment rate for all metropolitan areas in the United States.

-

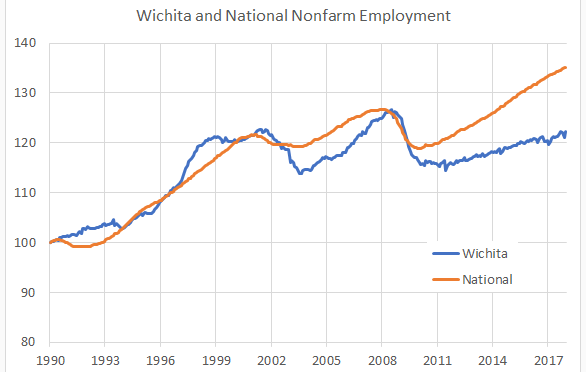

Wichita employment down, year-over-year

At a time Wichita leaders promote forward momentum in the Wichita economy, year-over-year employment has fallen.

-

Mayor Longwell’s pep talk

A column written by Wichita Mayor Jeff Longwell ignores the reality of Wichita’s economy.

-

Growing the Wichita economy

Wichita leaders are proud of our region’s economic growth. Here are the numbers.

-

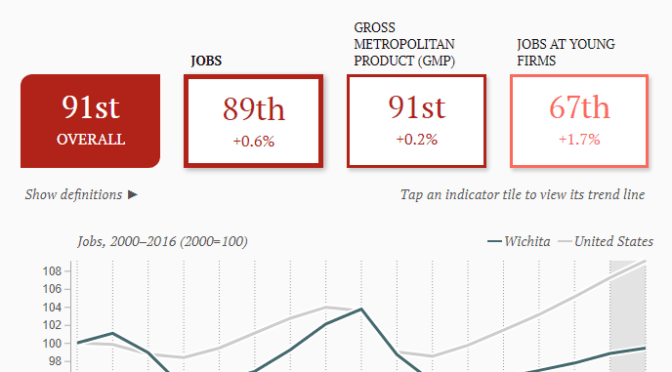

Metro Monitor evaluates the Wichita economy

Metro Monitor from Brookings Institution ranks metropolitan areas on economic performance. How does Wichita fare?

-

Greater Wichita Partnership asks for help

Wichita’s economic development agency asks for assistance in developing its focus and strategies.

-

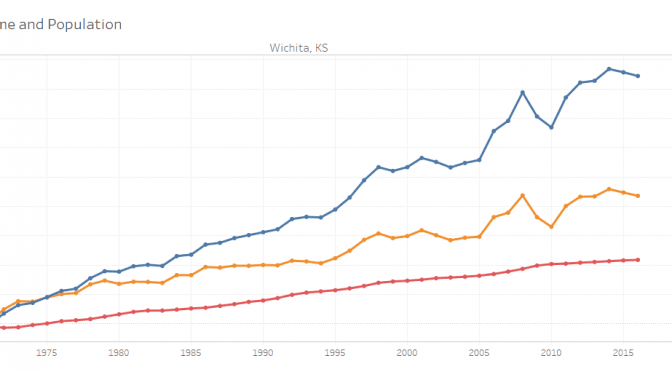

Wichita personal income up, a little

For 2016, personal income in Wichita rose, but is still below 2014 levels.

-

Wichita employment up

Employment in the Wichita metropolitan area is on an upward tick.