Tag: Taxation

-

Wichita tourism fee budget

The Wichita City Council will consider a budget for the city’s tourism fee paid by hotel guests.

-

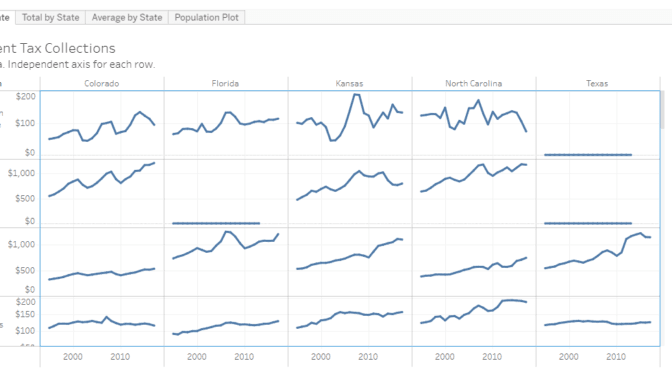

State government tax collections

An interactive visualization of tax collections by state governments.

-

Tax benefits for education don’t increase education

Here’s evidence of a government program that, undoubtedly, was started with good intentions, but hasn’t produced the intended results.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: United States Senator Dr. Tom Coburn

United States Senator Dr. Tom Coburn wrote the foreword to the book “What Was Really the Matter with the Kansas Tax Plan – The Undoing of a Good Idea.” He’s here to tell us what went wrong, and what we need to do.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Kansas Senator Ty Masterson

Kansas Senator Ty Masterson, a Republican from Andover, joins Bob and Karl to update us on happenings in the Kansas Legislature.

-

Wichita property tax rate: Down

The City of Wichita property tax mill levy declined for the second year in a row.

-

Naftzger Park private use plans unsettled

An important detail regarding Naftzger Park in downtown Wichita is unsettled, and Wichitans have reason to be wary.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: What Was Really the Matter with the Kansas Tax Plan

Dave Trabert of Kansas Policy Institute joins Bob and Karl to discuss his new book What Was Really the Matter with the Kansas Tax Plan –- The Undoing of a Good Idea.

-

What Was Really the Matter with the Kansas Tax Plan

Tax relief opponents have repeatedly pointed to the 2012 Kansas tax plan as their primary example of why tax cuts do not work. But, other states like North Carolina, Indiana, and Tennessee contemporaneously, and successfully, cut taxes. What was different about the Kansas experience?

-

In Wichita, three Community Improvement Districts to be considered

In Community Improvement Districts (CID), merchants charge additional sales tax for the benefit of the property owners, instead of the general public. Wichita may have an additional three, contributing to the problem of CID sprawl.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Radio Host Andy Hooser

Radio Host Andy Hooser of the Voice of Reason appears with Bob Weeks to discuss issues in state and national political affairs.

-

Spirit expands in Wichita

It’s good news that Spirit AeroSystems is expanding in Wichita. Let’s look at the cost.