Tag: Featured

-

From Pachyderm: Senate President Susan Wagle

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Kansas Senate President Susan Wagle. This was recorded February 1, 2019.

-

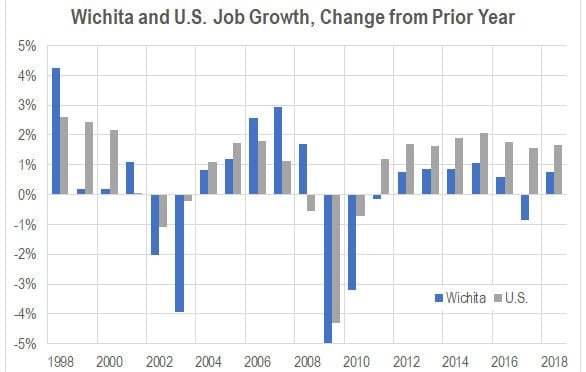

Wichita mayor promotes inaccurate picture of local economy

Wichita city leaders will latch onto any good news, no matter from how flimsy the source. But they ignore the news they don’t like, even though it may come from the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, or U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

-

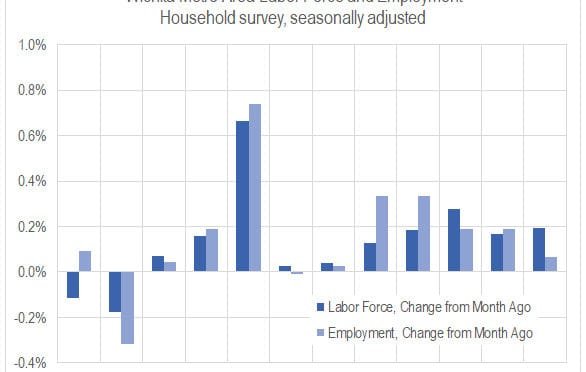

Wichita jobs and employment, December 2018

For the Wichita metropolitan area in December 2018, jobs are up, the labor force is up, and the unemployment rate is down when compared to the same month one year ago. Seasonal data shows a slowdown in the rate of job growth and a rising unemployment rate.

-

Wichita, a recession-proof city

Wichita city officials promote an article that presents an unrealistic portrayal of the local economy.

-

Job growth in Wichita: Great news?

A tweet from a top Wichita city official promotes great news that really isn’t so great.

-

Retiring Sedgwick County Commissioner Dave Unruh praised

The praise for retired Sedgwick County Commissioner Dave Unruh can’t be based on our region’s accomplishments under his guidance. That is, if people are informed and truthful.

-

In Wichita, a gentle clawback

Despite the mayor’s bluster, Wichita mostly lets a company off the hook.

-

Kansas jobs, December 2018

For Kansas in December 2018, a growing labor force and more jobs, but a slightly rising unemployment rate.

-

Wichita migration not improving

Data from the United States Census Bureau shows that the Wichita metropolitan area has lost many people to domestic migration, and the situation is not improving.

-

Wichita employment to grow in 2019

Jobs are forecasted to grow in Wichita in 2019, but the forecasted rate is low.

-

Unruh recollections disputed

A former Sedgwick County Commissioner disputes the narrative told by a retiring commissioner.

-

Taxpayers will miss Richard Ranzau

When a county commissioner’s questions produce a reversal of the county manager’s spending plans, you know we have good representation.