We have a lot of neat stuff in Wichita. Other cities do, too.

In New York Magazine, Oriana Schwindt writes in “The Unbearable Sameness of Cities: What my journey across the United States taught me about indie cafés and Ikea lights.”

I couldn’t stop noticing. I’d go on to see the same in Colorado Springs, in Fresno, in Indianapolis, in Oklahoma City, in Nashville.

And it wasn’t just the coffee shops — bars, restaurants, even the architecture of all the new housing going up in these cities looked and felt eerily familiar. Every time I walked into one of these places, my body would give an involuntary shudder. I would read over my notes for a city I’d visited months prior and find that several of my observations could apply easily to the one I was currently in.

In his commentary on this article, Aaron M. Renn wrote: “While every company tries its hardest to convince you of how much different and better it is than every other company in its industry, every city tries its hardest to convince you that it is exactly the same as every other city that’s conventionally considered cool.”

Later in the same piece, he wrote:

A challenge these places face is that the level of improvement locally has been so high, locals aren’t aware of how much the rest of the country has also improved. So they end up with an inflated sense of how much better they are doing versus the market. … People in these Midwest cities did not even know what was going on in the next city just 100 miles down the road. They were celebrating all these downtown condos being built. But the same condos were being built everywhere. … But even today people in most cities don’t really seem to get it that every city now has this stuff. Their city has dramatically improved relative to its own recent past, but it’s unclear how much it’s improved versus peers if at all.

Does this — the sameness of everywhere — apply to Wichita? Sure. Everyone thinks Wichita is different from everywhere else. We have a flag! A warehouse district! A Frank Lloyd Wright house! The NCAA basketball tournament! We’re (probably) getting a new baseball team and stadium!

We even have, as Schwindt does in cataloging what you’ll find in every single city mid-size and above, “Public murals that dare you to pass them without posing for a pic for the ‘gram.”

So many other places have this stuff, too.

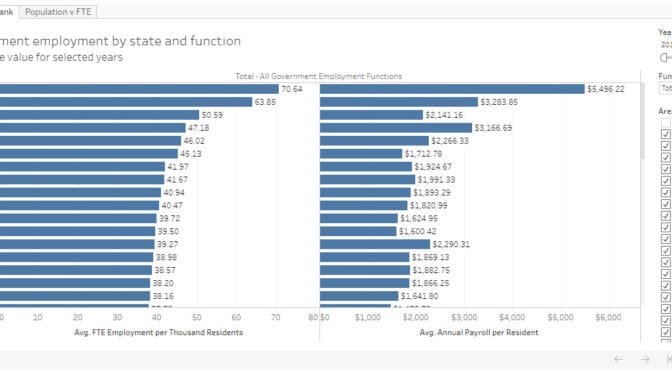

It isn’t bad that Wichita has these things. But the danger, as Renn notes, is that these things don’t distinguish Wichita. As much as we wish otherwise, these things are probably not going to reverse the course of the declining Wichita economy. If you don’t believe the Wichita economy is declining, consider that our GDP in 2016 was smaller than in the year before. Wichita metro employment growth was nonexistent during 2017, meaning it’s unlikely that GDP grew by much. (In January 2017 total non-farm employment in the Wichita MSA was 295,000. In January 2018 it was the same. See chart here.)

Even things that might really have a positive effect on the economy, like the Wichita State University Innovation Campus, are far from unique to Wichita. But developments like this are pitched to Wichitans as things that will really put Wichita on the map. A prosperous future is assured, we are told.

It’s great to love your city. But we can’t afford to be lulled into complacency — a false recognition of achievement — when all the data says otherwise.

We need a higher measure of honesty from our leaders. It might start with the mayor and the chair of the county commission, but the mayor seems terribly misinformed, as is the commission chair. Institutions that we ought to respect, like the local Chamber of Commerce, have presided over failing economic development but refuse to accept responsibility or even to acknowledge the facts. Worse, the Chamber spends huge amounts of money on blatantly dishonest campaigns against those candidates that don’t support its programs. Those programs, by the way, haven’t worked, if the goal of the Chamber is to grow the Wichita economy.