Tag: Interventionism

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Unknown stories of economic development, Uber, Fact-checking Yes Wichita

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: Wichita economic development, one more untold story. The arrival of Uber is a pivotal moment for Wichita. Fact-checking Yes Wichita on paved streets.

-

What incentives can Wichita offer?

Wichita government leaders complain that Wichita can’t compete in economic development with other cities and states because the budget for incentives is too small. But when making this argument, these officials don’t include all incentives that are available.

-

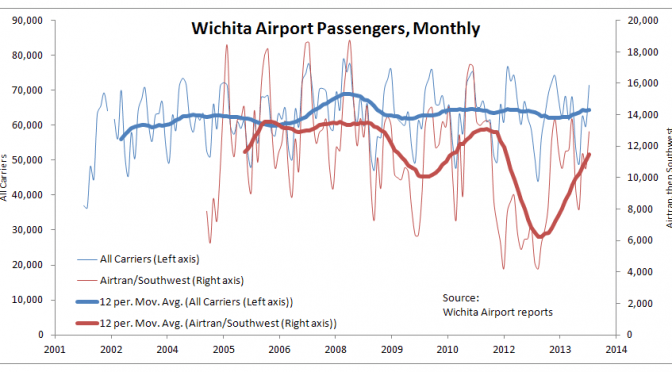

WichitaLiberty.TV: Issues surrounding the Wichita sales tax and airport

Who would be most harmed by the proposed Wichita sales tax? Also: A look at updated airport statistics, and what the city could do if it wants to pass the sales tax.

-

Wichita airport statistics updated

Why do Kansans pay taxes, including sales tax on food, to fund millions in subsidy to a company that is experiencing a sustained streak of record profits?

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Waste, economic development, and water issues.

Wichitans ought to ask city hall to stop blatant waste before it asks for more taxes. Then, a few questions about economic development incentives. Finally, how should we pay for a new water source, and is city hall open to outside ideas?

-

Economic development incentives in Wichita: A few questions

Wichita justifies its use of targeted economic development incentives by citing benefit-cost ratios that are computed for the city, county, school district, and state.

-

With new tax exemptions, what is the message Wichita sends to existing landlords?

As the City of Wichita prepares to grant special tax status to another new industrial building, existing landlords must be wondering why they struggle to stay in business when city hall sets up subsidized competitors with new buildings and a large cost advantage.

-

Wichita: We have incentives. Lots of incentives.

Wichita government leaders complain that Wichita can’t compete in economic development with other cities and states because the budget for incentives is too small. But when making this argument, these officials don’t include all incentives that are available.

-

What is the record of economic development incentives?

On the three major questions — Do economic development incentives create new jobs? Are those jobs taken by targeted populations in targeted places? Are incentives, at worst, only moderately revenue negative? — traditional economic development incentives do not fare well.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Old Town, Economic development incentives, and waste in Wichita

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: A look at a special district proposed for Old Town, the process of granting economic development incentives and a cataloging of the available tools and amounts, and an example of waste in Wichita.

-

Contrary to officials, Wichita has many incentive programs

Wichita government leaders complain that Wichita can’t compete in economic development with other cities and states because the budget for incentives is too small. But when making this argument, these officials don’t include all incentives that are available.

-

Few Wichitans support taxation for economic development subsidies

In Wichita, about one-third of voters polled support local governments using taxpayer money to provide subsidies to certain businesses for economic development.