Tag: Kansas Policy Institute

-

Wichita voters’ opinion of city spending

As Wichita voters prepare to decide on the proposed one cent per dollar sales tax, a recent survey found that few voters believe the city spends efficiently.

-

Moving Wichitans in the Future: Paving and Transit Via Sales Tax?

From Kansas Policy Institute, the third and final free conference examining issues related to the proposed one cent per dollar Wichita sales tax.

-

Where is Duane Goossen, former Kansas budget director?

Kansans are being inundated with the false choice of tax increases or service reductions, all for political gain, writes Dave Trabert of Kansas Policy Institute.

-

Wichita Water Task Force findings presented

Karma Mason, President of iSi Environmental, presents the Water Task Force Findings from the Wichita Chamber of Commerce during the Wichita Water Conference.

-

For Wichita Chamber’s expert, no negatives to economic development incentives

An expert in economic development sponsored by the Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce tells Wichita there are no studies showing that incentives don’t work.

-

Kansas schools shortchanged

Kansas schools could receive $21 million annually in federal funds if the state had adequate information systems in place.

-

To Wichita, a promise to wisely invest if sales tax passes

Claims of a reformed economic development process if Wichita voters approve a sales tax must be evaluated in light of past practice and the sameness of the people in charge. If these leaders are truly interested in reforming Wichita’s economic development machinery and processes, they could have started years ago using the generous incentives we…

-

For Kansas budget, balance is attainable

A policy brief from a Kansas think tank illustrates that balancing the Kansas budget while maintaining services and lower tax rates is not only possible, but realistic.

-

For Wichita city hall, an educational opportunity

Will Wichita city officials and sales tax boosters attend an educational event produced by a leading Kansas public policy institute? It will be an opportunity for city officials to demonstrate their commitment to soliciting input from the community.

-

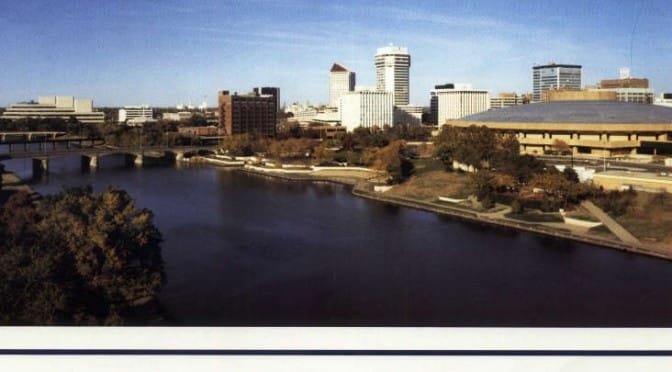

Fostering economic growth in Wichita

Kansas Policy Institute is hosting a conference titled “Fostering Economic Growth in Wichita,” focusing on the economic development, or jobs, portion of the proposed sales tax.

-

Public opinion on Wichita sales tax

As Wichita prepares to debate the desirability of a sales tax increase, a public opinion poll finds little support for the tax and the city’s plans.

-

What is truth on education finance in Kansas?

One must wonder how much of Kansas’ and the nation’s student achievement woes are attributable to political self-interest and putting a higher priority on institutions than on the needs of individual students, writes Dave Trabert of Kansas Policy Institute.