Tag: STAR bonds

-

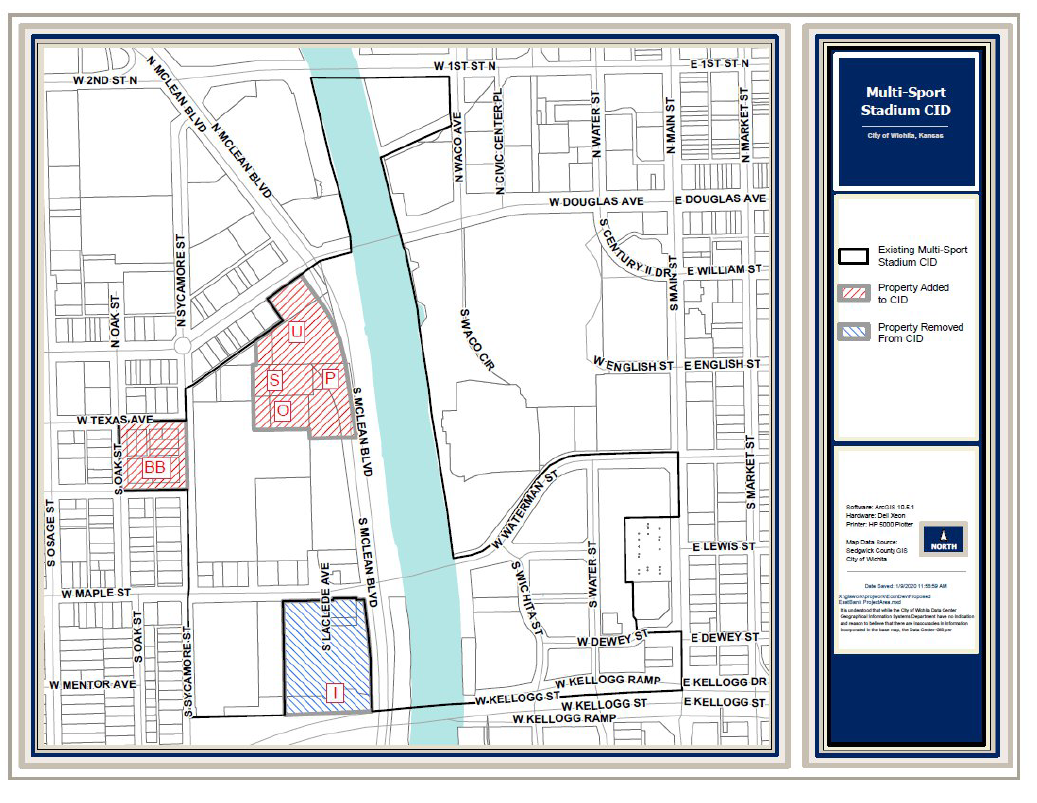

Wichita taxing district to expand

The City of Wichita plans to expand a special tax district.

-

Wichita considers a new stadium

The City of Wichita plans subsidized development of a sports facility as an economic driver. Originally published in July 2017.

-

From Pachyderm: Economic development incentives

A look at some of the large economic development programs in Wichita and Kansas.

-

In Wichita, spending semi-secret

The Wichita City Council authorized the spending of a lot of money without discussion.

-

In Wichita, new stadium to be considered

The City of Wichita plans subsidized development of a sports facility as an economic driver.

-

On Wichita’s STAR bond promise, we’ve heard it before

Are the City of Wichita’s projections regarding subsidized development as an economic driver believable?

-

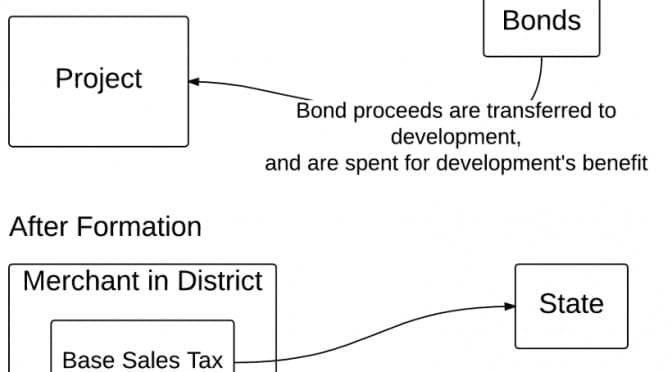

Kansas economic development programs

Explaining common economic development programs in Kansas.

-

In Wichita, an incomplete economic development analysis

The Wichita City Council will consider an economic development incentive based on an analysis that is nowhere near complete.

-

In Wichita, benefitting from your sales taxes, but not paying their own

A Wichita real estate development benefits from the sales taxes you pay, but doesn’t want to pay themselves.