Tag: Wichita city government

-

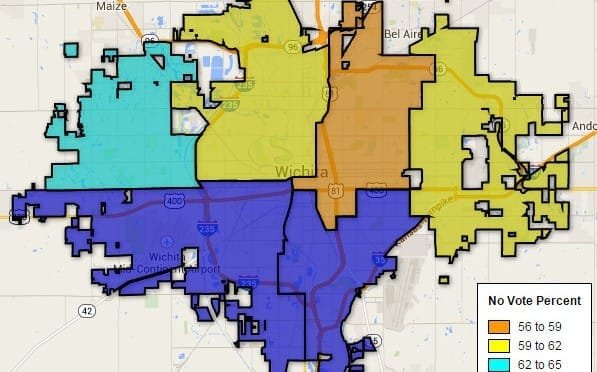

Wichita sales tax election map by district

Here’s a map I created of the “No” vote percentage by council district.

-

Wichita Mayor Carl Brewer on citizen engagement

Wichita Mayor Carl Brewer and the city council are proud of their citizen engagement efforts. Should they be proud?

-

Wichita Mayor Carl Brewer should stand down on tax projects

Despite the stunning defeat of Wichita Mayor Carl Brewer’s proposed sales tax increase, and the fact that in April Brewer’s term limit will expire, he and the City Council are determined to take action in financing the projects that the Wichita voters just shot down, writes Mike Shatz.

-

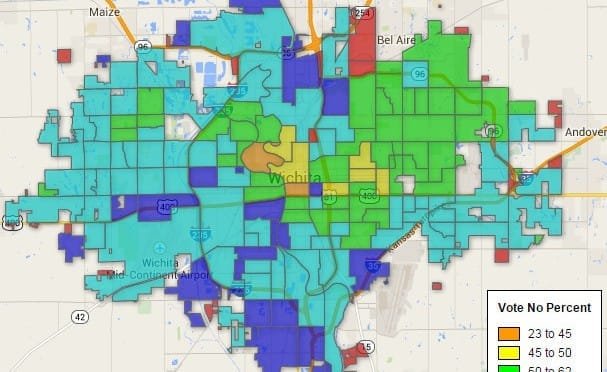

Wichita sales tax election map

Here’s a map I created of the “No” vote percentage by precinct.

-

In election coverage, The Wichita Eagle has fallen short

Citizens want to trust their hometown newspaper as a reliable source of information. The Wichita Eagle has not only fallen short of this goal, it seems to have abandoned it.

-

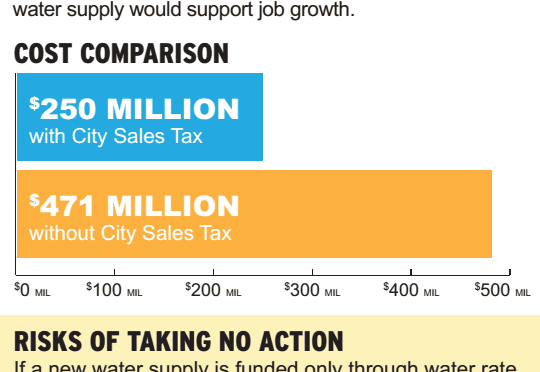

Fact-checking Yes Wichita: Water pipe(s)

The “Yes Wichita” campaign group makes a Facebook post with false information to Wichita voters. Will Wichita Mayor Carl Brewer send a mailer to Wichitans warning them of this misleading information?

-

Wichita to consider tax exemptions

A Wichita company asks for property and sales tax exemptions on the same day Wichita voters decide whether to increase the sales tax, including the tax on groceries.

-

Fact-checking Yes Wichita: Tax rates

The claim that the mill levy has not been raised for a long time is commonly made by the city and “Yes Wichita” supporters. It’s useful to take a look at actual numbers to see what has happened.

-

While campaigning for higher sales tax, the Wichita Chamber president seeks an extension of his exemption from that tax

Campaigning for higher sales tax on groceries for low-income households while you ask for an extension of your company’s exemption from paying sales tax is, well, awkward.

-

Wichita Mayor Carl Brewer is concerned about misinformation

Wichita Mayor Carl Brewer is concerned about misinformation being spread regarding the proposed Wichita sales tax.

-

‘Yes Wichita’ co-chairs serve up contradicting plans for sales tax revenue

At two forums on the proposed Wichita sales tax, leaders of the “Yes Wichita” group provided contradicting visions for plans for economic development spending, and for its oversight.

-

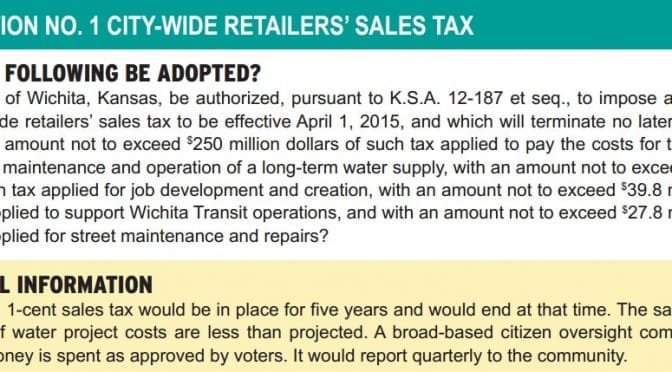

Another Wichita sales tax forum

On Wednesday October 29 KCTU Television held a televised debate on the issue of the proposed one cent per dollar Wichita sales tax.