Tag: Featured

-

The use of sales tax proceeds in Wichita

Must the City of Wichita spend its share of Sedgwick County sales tax proceeds in a specific way?

-

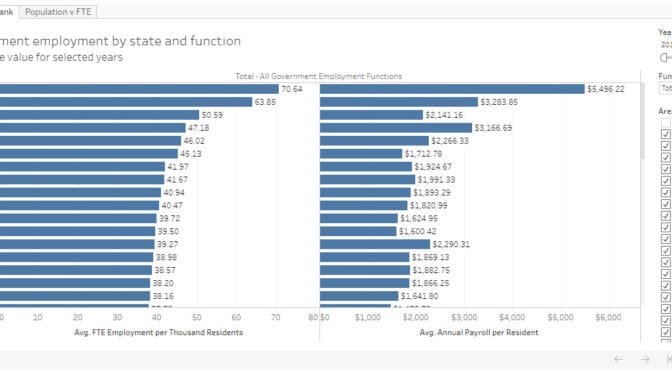

State government employees in Kansas

Kansas has more state government employees per resident than most states, and the trend is rising.

-

More TIF spending in Wichita

The Wichita City Council will consider approval of a redevelopment plan in a tax increment financing (TIF) district.

-

Wichita Wingnuts settlement: There are questions

It may be very expensive for the City of Wichita to terminate its agreement with the Wichita Wingnuts baseball club, and there are questions.

-

Kansas state and local taxes

Among nearby states, Kansas collects a lot of taxes, on a per-resident basis.

-

From Pachyderm: Sedgwick County Commission candidates

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Republican Candidates for Sedgwick County Commission. Appearing, in order of their initial appearance, were: Richard Ranzau running in District 4, Pete Meitzner in District 1, and Jim Howell in District 5.

-

Wichita, not that different

We have a lot of neat stuff in Wichita. Other cities do, too.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Kansas gubernatorial candidate Greg Orman

Independent candidate for Kansas governor Greg Orman joins Bob and Karl to explain why he should be our next governor.

-

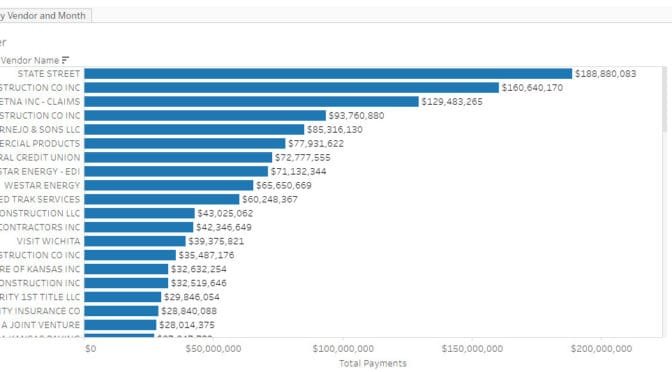

Wichita checkbook updated

Wichita spending data presented as a summary, and as a list.

-

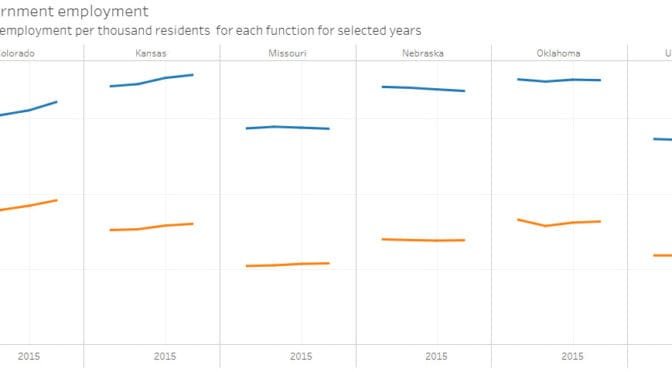

Local government employment in Kansas

Kansas has nearly the highest number of local government employees per resident, compared to other states.

-

From Pachyderm: Kansas House of Representatives Candidates

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Kansas House of Representatives Candidates. These are Republican candidates appearing on the November 6, 2018 general election ballot.

-

Wichita being sued, alleging improper handling of bond repayment savings

A lawsuit claims that when the City of Wichita refinanced its special assessment bonds, it should have passed on the savings to the affected taxpayers, and it did not do that.