From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Kansas Treasurer Jake LaTurner. This was recorded on September 14, 2018.

Shownotes

- Kansas State Treasurer: www.kansasstatetreasurer.com

- Jake LaTurner for Kansas State Treasurer: www.jakelaturner.com

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Kansas Treasurer Jake LaTurner. This was recorded on September 14, 2018.

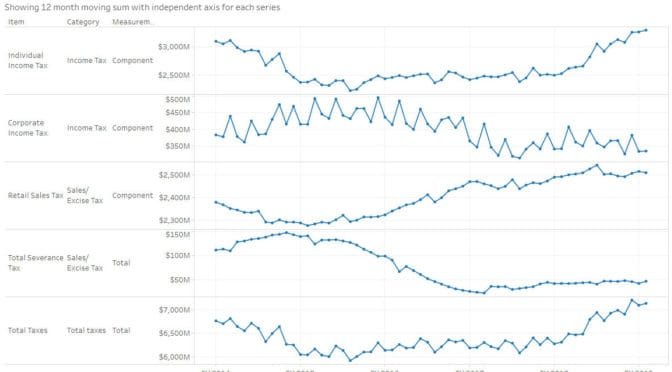

Kansas tax receipts by category, presented in an interactive visualization.

The Kansas Division of the Budget publishes monthly statistics regarding tax collections. I’ve gathered these and present them in an interactive visualization.

In the nearby example from the visualization, we can see the rising trend in individual income taxes, due to the tax increase passed by the Kansas Legislature.

Click here to learn more and access the visualization.

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: Libertarian Party candidate for Kansas governor Jeff Caldwell joins Bob and Karl to explain why he should be our next governor. View below, or click here to view at YouTube. Episode 209, broadcast September 16, 2018.

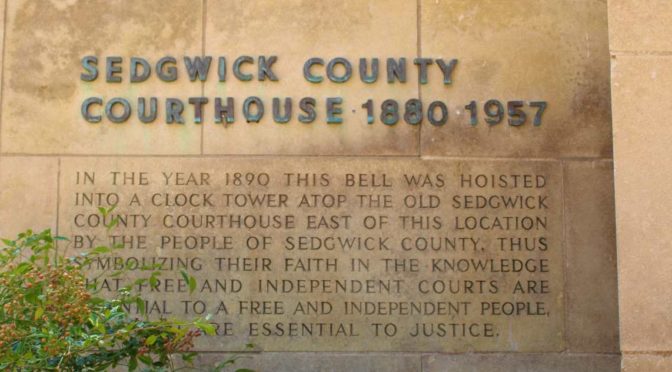

Must the City of Wichita spend its share of Sedgwick County sales tax proceeds in a specific way?

Sedgwick County collects a one-cent per dollar retail sales tax. The county keeps some, then distributes the rest to cities. On Facebook, a question arose regarding how Wichita may spend its share of the sales tax proceeds. Couldn’t some funds that go towards building Kellogg be rerouted to, say, fund the operations of Wichita’s public library system?

A former city council member argued that “As it stands, Wichita cannot spend its allocated portion of that sales tax on anything but roads and bridges.” I posted that there was a Wichita city ordinance that said how the sales tax is to be spent in Wichita, and that ordinance could be modified or canceled. The same former council member admonished me to call a specific person in the city budget office and “he will clarify for you that the City Council doesn’t have the ability to override the Sedgwick County sales tax referendum language.”

I looked for the referendum language. The document is available in Sedgwick County’s election document system. The canvass of the special sales tax election was held on August 2, 1985, and this was reported:

The returns of the election were presented to the Board as received from the official conducting the election on the following proposition:

SHALL THE FOLLOWING BE ADOPTED?

A proposition to enact a countywide retailers’ sales tax in Sedgwick County, Kansas, in the amount of one percent (1%), such tax to take effect on October 1, 1985, pursuant to K.S.A. 1984 Supp. 12-187.

The language of the referendum is silent regarding how the tax revenue may or may not be spent.

Second, there is a Wichita city ordinance, number 41-185. It pledges half the city’s share of the sales tax towards property tax reduction. Then, it states: “… and pledges the remaining one half of the one percent (1%) of any revenues received to Wichita road, highway and bridge projects including right-of-way acquisitions.” This was adopted on August 25, 1992 and replaced an existing ordinance that said the same.

The 1992 ordinance also holds this, in section II: “It is the specific intent of the Governing Body of the City of Wichita that the City of Wichita continue to use the tax revenues as outlined in this ordinance and that this pledge be continued as a matter of faith and trust between the people and the present and future Governing Bodies of the City of Wichita.”

We often hear that half the city’s share of the sales tax is pledged for Kellogg construction. In actuality it is pledged to “Wichita road, highway and bridge projects.”

But really, it isn’t even pledged to that. The pledge is in the form of a city ordinance. It may be changed at any time at the will of four council members.

Yes, the ordinance says the city intends to continue using the tax revenues in the same way “as a matter of faith and trust.” Unfortunately, that trust has been destroyed in many ways, one being council members who tell us things that aren’t true.

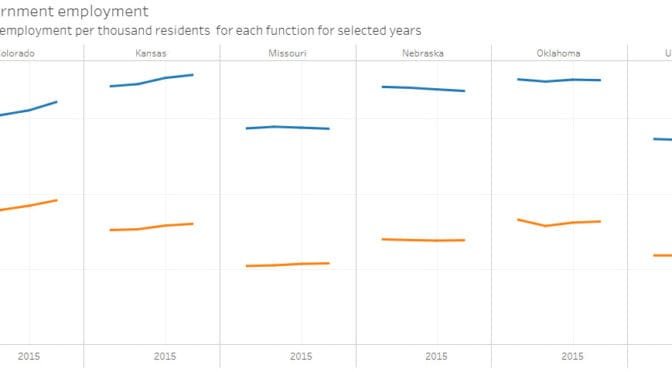

Kansas has more state government employees per resident than most states, and the trend is rising.

Each year the United States Census Bureau surveys federal, state, and local government civilian employees. 1 The amount of payroll for a single month (March) is also recorded. In this case, I’ve made the data for state government employees available in an interactive visualization.

For 2016, Kansas had 17.90 full-time equivalent state government employees per thousand residents. This ranked 15th among the states. These employees resulted in payroll cost of $979 per resident, which is 21st among the states.

Nearby is an example from the visualization showing state government employment count (full-time equivalent) per thousand residents for Kansas and some nearby states. It shows total employment, and in addition, education employment and hospital employment. (Since nearly all employees in Kansas elementary and secondary schools are employees of local government, not the state, the employees shown are working in higher education. See below for visualizations of local government employees.)

Two things are evident: The level of employment in Kansas is generally higher than the other states, and the trend in Kansas is rising when many states are level or declining. This data counters the story often told, which is that state government employment has been slashed.

If we look at data for state and local government employees, the conclusions are nearly the same.

Click here to learn more and access the visualization.

There are separate visualizations for local government employees only, and also for state and local government employees together. Click on state and local government employment or local government employment by state and function.

—

Notes

The Wichita City Council will consider approval of a redevelopment plan in a tax increment financing (TIF) district.

This week the Wichita City Council will hold a public hearing considering approval of more tax increment financing (TIF) spending in downtown Wichita. The spending is for the second phase of redevelopment of the Union Station property on East Douglas. According to city documents, the total cost of this phase is $31,000,000, with TIF paying for $2,954,734. 1

This is a pay-as-you-go form of TIF, which means the city does not borrow funds as it would in a traditional TIF district. Instead, the eligible portion of the developer’s property taxes will be rerouted back to the development as they are paid.

The TIF district was established in 2014. The council this week considers a redevelopment plan, which authorizes spending TIF funds on a specific project. Redevelopment plans must be approved by a two-thirds majority of the council. While overlapping jurisdictions like counties and school districts can block the formation of a TIF district, they have no such role in the approval of a redevelopment plan.

Of note, this public hearing is being held after the fact, sort of. City documents state: “A development agreement was approved by the City Council on August 7, to allow for the developer to begin non-TIF eligible improvements in order to meet deadlines for a new tenant.” The city documents for the August 7 meeting hold this: 2

The Developer has requested that the development agreement be approved now, prior to adoption of the project plan, to allow work to begin on the Meade Corridor improvements in order to complete the project in time for the tenant to move in. The Development agreement is drafted to allow for the Meade Corridor improvements to occur following adoption of the agreement, however, any work or reimbursement for TIF is contingent on City Council adoption of the project plan following the September 11 public hearing.

Citizens have to wonder will the September 11 public hearing have any meaning or relevance, given that on August 7 the city gave its de facto approval of the redevelopment plan.

Following, more information about tax increment financing.

Tax increment financing disrupts the usual flow of tax dollars, routing funds away from cash-strapped cities, counties, and schools back to the TIF-financed development. TIF creates distortions in the way cities develop, and researchers find that the use of TIF means lower economic growth.

A TIF district is a geographically-defined area.

In Kansas, TIF takes two or more steps. The first step is that cities or counties establish the boundaries of the TIF district. After the TIF district is defined, cities then must approve one or more project plans that authorize the spending of TIF funds in specific ways. (The project plan is also called a redevelopment plan.) In Kansas, overlapping counties and school districts have an opportunity to veto the formation of the TIF district, but this rarely happens. Once the district is formed, cities and counties have no ability to object to TIF project plans.

(Cities, counties, and school districts still receive the base tax payments, but these are usually small, much smaller than the incremental taxes. In non-TIF development, these agencies still receive the base taxes too, plus whatever taxes result from improvement of the property — the “increment,” so to speak. Or simply, all taxes.)

The Kansas law governing TIF, or redevelopment districts as they are also called, starts at K.S.A. 12-1770.

Originally most states included a “but for” test that TIF districts must meet. That is, the proposed development could not happen but for the benefits of TIF. Many states have dropped this requirement. At any rate, developers can always present proposals that show financial necessity for subsidy, and gullible government officials will believe.

Similarly, TIF was originally promoted as a way to cure blight. But cities are so creative and expansive in their interpretation of blight that this requirement, if it still exists, has little meaning.

The rerouting of property taxes under TIF goes against the grain of the way taxes are usually rationalized. We use taxation as a way to pay for services that everyone benefits from, and from which we can’t exclude people. An example would be police protection. Everyone benefits from being safe, and we can’t exclude people from benefiting from police protection.

So when we pay property tax — or any tax, for that matter — people may be comforted knowing that it goes towards police and fire protection, street lights, schools, and the like. (Of course, some is wasted, and government is not the only way these services, especially education, could be provided.)

But TIF is contrary to this justification of taxes. TIF allows property taxes to be used for one person’s (or group of persons) exclusive benefit. This violates the principle of broad-based taxation to pay for an array of services for everyone. Remember: What was the purpose of the TIF bonds? To pay for things that benefited the development. Now, the development’s property taxes are being used to repay those bonds instead of funding government.

One more thing: Defenders of TIF will say that the developers will pay all their property taxes. This is true, but only on a superficial level. We now see that the lion’s share of the property taxes paid by TIF developers are routed back to them for their own benefit.

In their justification of TIF in general, or specific projects, proponents may say that TIF dollars are spent only on allowable purposes. Usually a prominent portion of TIF dollars are spent on infrastructure. This allows TIF proponents to say the money isn’t really being spent for the benefit of a specific project. It’s spent on infrastructure, they say, which they contend is something that benefits everyone, not one project specifically. Therefore, everyone ought to pay.

This attitude is represented by a comment left at Voice for Liberty, which contended: “The thing is that real estate developers do not invest in public streets, sidewalks and lamp posts, because there would be no incentive to do so. Why spend millions of dollars redoing or constructing public streets when you can not get a return on investment for that”

This perception is common: that when we see developers building something, the City of Wichita builds the supporting infrastructure at no cost to the developers. But it isn’t quite so. About a decade ago a project was being developed on the east side of Wichita, the Waterfront. This project was built on vacant land. Here’s what I found when I searched for City of Wichita resolutions concerning this project:

In a TIF district, these things are called “infrastructure” and will be paid for by the development’s own property taxes — taxes that must be paid in any case. Outside of TIF districts, developers pay for these things themselves.

Generally, TIF is justified using the “but-for” argument. That is, nothing will happen within a district unless the subsidy of TIF is used. Paul F. Byrne explains:

“The but-for provision refers to the statutory requirement that an incentive cannot be awarded unless the supported economic activity would not occur but for the incentive being offered. This provision has economic importance because if a firm would locate in a particular jurisdiction with or without receiving the economic incentive, then the economic impact of offering the incentive is non-existent. … The but-for provision represents the legislature’s attempt at preventing a local jurisdiction from awarding more than the minimum incentive necessary to induce a firm to locate within the jurisdiction. However, while a firm receiving the incentive is well aware of the minimum incentive necessary, the municipality is not.”

It’s often thought that when a but-for justification is required in order to receive an economic development incentive, financial figures can be produced that show such need. Now, recent research shows that the but-for justification is problematic. In Does Chicago’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Programme Pass the ‘But-for’ Test? Job Creation and Economic Development Impacts Using Time-series Data, author T. William Lester looked at block-level data regarding employment growth and private real estate development. The abstract of the paper describes:

“This paper conducts a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of Chicago’s TIF program in creating economic opportunities and catalyzing real estate investments at the neighborhood scale. This paper uses a unique panel dataset at the block group level to analyze the impact of TIF designation and investments on employment change, business creation, and building permit activity. After controlling for potential selection bias in TIF assignment, this paper shows that TIF ultimately fails the ‘but-for’ test and shows no evidence of increasing tangible economic development benefits for local residents.” (emphasis added)

In the paper, the author clarifies:

“To clarify these findings, this analysis does not indicate that no building activity or job crea-tion occurred in TIFed block groups, or resulted from TIF projects. Rather, the level of these activities was no faster than similar areas of the city which did not receive TIF assistance. It is in this aspect of the research design that we are able to conclude that the development seen in and around Chicago’s TIF districts would have likely occurred without the TIF subsidy. In other words, on the whole, Chicago’s TIF program fails the ‘but-for’ test.

Later on, for emphasis:

“While the findings of this paper are clear and decisive, it is important to comment here on their exact extent and external validity, and to discuss the limitations of this analysis. First, the findings do not indicate that overall employment growth in the City of Chicago was negative or flat during this period. Nor does this research design enable us to claim that any given TIF-funded project did not end up creating jobs. Rather, we conclude that on-average, across the whole city, TIF was unsuccessful in jumpstarting economic development activity — relative to what would have likely occurred otherwise.” (emphasis in original)

The author notes that these conclusions are specific to Chicago’s use of TIF, but should “should serve as a cautionary tale.”

The paper reinforces the problem of using tax revenue for private purposes, rather than for public benefit: “Essentially, Chicago’s extensive use of TIF can be interpreted as the siphoning off of public revenue for largely private-sector purposes. Although, TIF proponents argue that the public receives enhanced economic opportunity in the bargain, the findings of this paper show that the bargain is in fact no bargain at all.”

TIF represents social engineering. By using it, city government has decided that it knows best where development should be directed. In particular, the Wichita city council has decided that Old Town and downtown development is on a superior moral plane to other development. Therefore, we all have to pay higher taxes to support this development. What is the basis for saying Old Town developers don’t have to pay for their infrastructure, but developers in other parts of the city must pay?

Does TIF work? It depends on what the meaning of “work” is.

If by working, do we mean does TIF induce development? If so, then TIF usually works. When the city authorizes a TIF project plan, something usually gets built or renovated. But this definition of “works” must be tempered by a few considerations.

Does TIF pay for itself?

First, is the project self-sustaining? That is, is the incremental property tax revenue sufficient to repay the TIF bonds? This has not been the case with all TIF projects in Wichita. The city has had to bail out two TIFs, one with a no-interest and low-interest loan that cost city taxpayers an estimated $1.2 million.

The verge of corruption

Second, does the use of TIF promote a civil society, or does it lead to cronyism? Randal O’Toole has written:

“TIF puts city officials on the verge of corruption, favoring some developers and property owners over others. TIF creates what economists call a moral hazard for developers. If you are a developer and your competitors are getting subsidies, you may simply fold your hands and wait until someone offers you a subsidy before you make any investments in new development. In many cities, TIF is a major source of government corruption, as city leaders hand tax dollars over to developers who then make campaign contributions to re-elect those leaders.”

We see this in Wichita, where the regular recipients of TIF benefits are also regular contributors to the political campaigns of those who are in a position to give them benefits. The corruption is not illegal, but it is real and harmful, and calls out for reform. See In Wichita, the need for campaign finance reform.

The effect of TIF on everyone

Third, what about the effect of TIF on everyone, that is, the entire city or region? Economists have studied this matter, and have concluded that in most cases, the effect is negative.

An example are economists Richard F. Dye and David F. Merriman, who have studied tax increment financing extensively. Their article Tax Increment Financing: A Tool for Local Economic Development states in its conclusion:

“TIF districts grow much faster than other areas in their host municipalities. TIF boosters or naive analysts might point to this as evidence of the success of tax increment financing, but they would be wrong. Observing high growth in an area targeted for development is unremarkable.”

So TIF districts are good for the favored development that receives the subsidy — not a surprising finding. What about the rest of the city? Continuing from the same study:

“If the use of tax increment financing stimulates economic development, there should be a positive relationship between TIF adoption and overall growth in municipalities. This did not occur. If, on the other hand, TIF merely moves capital around within a municipality, there should be no relationship between TIF adoption and growth. What we find, however, is a negative relationship. Municipalities that use TIF do worse.

We find evidence that the non-TIF areas of municipalities that use TIF grow no more rapidly, and perhaps more slowly, than similar municipalities that do not use TIF.” (emphasis added)

In a different paper (The Effects of Tax Increment Financing on Economic Development), the same economists wrote “We find clear and consistent evidence that municipalities that adopt TIF grow more slowly after adoption than those that do not. … These findings suggest that TIF trades off higher growth in the TIF district for lower growth elsewhere. This hypothesis is bolstered by other empirical findings.” (emphasis added)

The Wichita city council is concerned about creating jobs, and is easily swayed by the promises of developers that their establishments will create jobs. Paul F. Byrne of Washburn University has examined the effect of TIF on jobs. His recent report is Does Tax Increment Financing Deliver on Its Promise of Jobs? The Impact of Tax Increment Financing on Municipal Employment Growth, and in its abstract we find this conclusion regarding the impact of TIF on jobs:

“This article addresses the claim by examining the impact of TIF adoption on municipal employment growth in Illinois, looking for both general impact and impact specific to the type of development supported. Results find no general impact of TIF use on employment. However, findings suggest that TIF districts supporting industrial development may have a positive effect on municipal employment, whereas TIF districts supporting retail development have a negative effect on municipal employment. These results are consistent with industrial TIF districts capturing employment that would have otherwise occurred outside of the adopting municipality and retail TIF districts shifting employment within the municipality to more labor-efficient retailers within the TIF district.” (emphasis added)

These studies and others show that as a strategy for increasing the overall wellbeing of a city, TIF fails to deliver prosperity, and in fact, causes harm.

—

Notes

It may be very expensive for the City of Wichita to terminate its agreement with the Wichita Wingnuts baseball club, and there are questions.

As the City of Wichita prepares to build a new stadium for a new baseball team, there is the issue of the old stadium and the old team. The city has decided that the old stadium will be razed. On Tuesday the city council will consider what to do about the old team.

The old team, the Wichita Wingnuts, has a lease agreement with the city. The lease is from January 2015 and is for a period of ten years. The documents, both the lease from 2015 and the proposed settlement to be considered this week, appear in full in Wichita city council agenda packets. I’ve extracted the relevant pages for easier access. Click on lease or proposed settlement.

According to the settlement, the Wingnuts will receive either $2.2 million or $1.2 million, the smaller amount applying in the case the city is “unable to reach an agreement with an affiliated minor league baseball team in the year 2018.” The payment is scheduled to be made in installments over the next several years. (Section 2c)

Reading the lease, I can’t find anything regarding the need to pay for terminating the lease. So why the need to pay up to $2.2 million to terminate?

Here’s a possible answer: City documents hold this: “This negotiated settlement resolves all claims and potential claims that the parties have or may have, including breach of the Lease, loss of revenue, injunctive relief, specific performance, other contract breaches, tort assertions, and claims for equitable relief without the uncertainly of litigation.”

So there may be disputes that need to be resolved. Now the question becomes this: What did the city do? What could be so bad that the remedy is to pay the Wingnuts up to $2.2 million? Citizens ought to know the answer to this question.

Further, why is the amount of the settlement contingent on what happens in Wichita in the future? (Remember, the settlement is $2.2 million if the city lands a new team, but only $1.2 million if it doesn’t.) If the purpose of the settlement is to compensate the Wingnuts for harm caused by the city, how and why is the magnitude of harm dependent on future events?

Such a large settlement is especially surprising given the low rent the Wingnuts paid and the city’s history with the Wingnuts as a tenant. Consider:

The Wingnuts didn’t always pay their rent. The city charged the Wingnuts just $25,000 annual rent, and the team was $77,000 behind in rent in January 2015. The proposed settlement agreement states: “As of the Effective Date, the 2018 rent payment in the amount of Twenty-five Thousand Dollars ($25,000) due and payable by WIB to the City shall be waived and no longer due and payable by WIB.” (Section 2c) (WIB is the company that owns the Wingnuts.)

There have also been disputes over utility payments. But, the city will forgive the water and sewer bill: “The City shall pay all utility payments due to the Department of Public Works and Utilities that are assessed for 2018.” (Section 2d)

It’s clear that the Wingnuts haven’t always lived up to the basics of its agreement with the city. Why, then, does the city feel such a large obligation upon termination? Paragraph 13 of the lease says “Lessor agrees not to utilize termination for convenience for the purpose of placing any professional baseball franchise at the Lawrence-Dumont Stadium site.” This is what the city is doing. But, in paragraph 23: “The parties agree that upon a violation of any provision of this lease, the aggrieved party may, at its option, terminate this lease by giving the breaching party not less than 30 days written notice of termination.” Non-payment of rent seems like it ought to be a violation of the lease, giving the city the right to terminate the lease for cause.

What is the source of the $2.2 million? City documents state the source is “management agreement payments paid by the new AAA baseball team.” The meaning of “management agreement payments” is unclear and a question that needs an answer. But presumably this is money that the city would receive from the new team. If not paid to the Wingnuts, these funds might be available for other purposes.

And: If the city is not able to land a new team, the city will have to pay the Wingnuts $1.2 million without any compensating revenue source.

Here’s a puzzling aspect of the settlement: How was the dollar amount determined? City documents state: “The value of the severance is based on the number of years remaining in the existing lease and the anticipated City financial cost of capital repairs, replacements and improvements over those same remaining years.” (emphasis added)

What? “Repairs, replacements and improvements” to a stadium that will be demolished soon? Why is this a consideration?

There are questions, but little time for answers. The agenda packet was posted on the city’s website on Friday September 7, at 12:03 pm. The council will consider this item Tuesday morning.

Do council members have answers to these questions? Some of these matters may have been discussed in executive session. Now that the matters have been settled, it’s time to let citizens know the details.

But if council members don’t have answers, I don’t think they can make an informed vote.

Among nearby states, Kansas collects a lot of taxes, on a per-resident basis.

The United States Census Bureau collects data from the states regarding tax collections. Some data is available for each quarter subdivided by category.

From the first quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2018, Kansas and its local governmental units collected an average of $681 per quarter per resident in taxes. Of nearby states and a few others, Arkansas and Iowa had higher values, and Iowa is higher by only one percent.

From the first quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2018, Kansas and its local governmental units collected an average of $681 per quarter per resident in taxes. Of nearby states and a few others, Arkansas and Iowa had higher values, and Iowa is higher by only one percent.

Some states had lower values, such as Colorado at $565 per quarter per resident (17.0 percent less than Kansas), Texas and Missouri both at $486 (28.6 percent less), and Florida at $470 (31.0 percent less).

To learn more about this visualization and create your own, click here.

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Republican Candidates for Sedgwick County Commission. Appearing, in order of their initial appearance, were:

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Republican Candidates for Sedgwick County Commission. Appearing, in order of their initial appearance, were:

This was recorded September 7, 2018.