Tag: Featured

-

From Pachyderm: Congressman Mike Pompeo

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Congressman Mike Pompeo delivered an update on the issues of the day and answered questions.

-

In Wichita, developer welfare under a cloud

A downtown Wichita project receives a small benefit from the city, with no mention of the really big money.

-

Kansas school fund balances

Kansas school fund balances rose significantly this year, in both absolute dollars and dollars per pupil.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Radio host Andy Hooser

Radio show host Andy Hooser visits the KGPT studios to talk about upcoming elections in Kansas and the presidential campaign.

-

Topeka Capital-Journal falls for a story

The editorial boards of two large Kansas newspapers have shown how little effort goes into forming the opinions they foist upon our state.

-

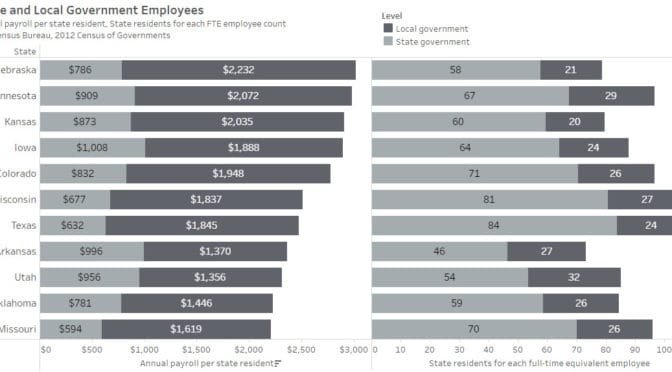

Kansas, a frugal state?

Is Kansas a frugal state, compared to others?

-

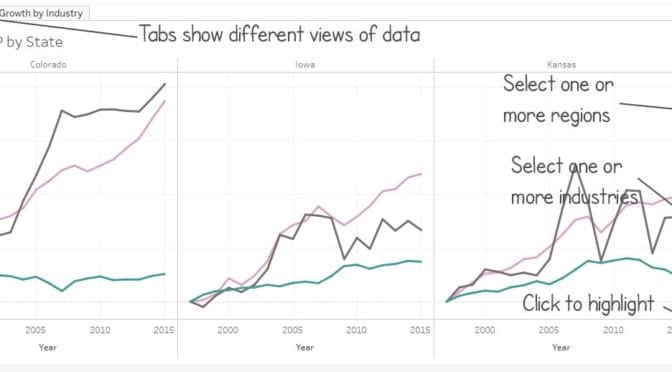

GDP by state and component

An interactive visualization of gross domestic product by state and industry.

-

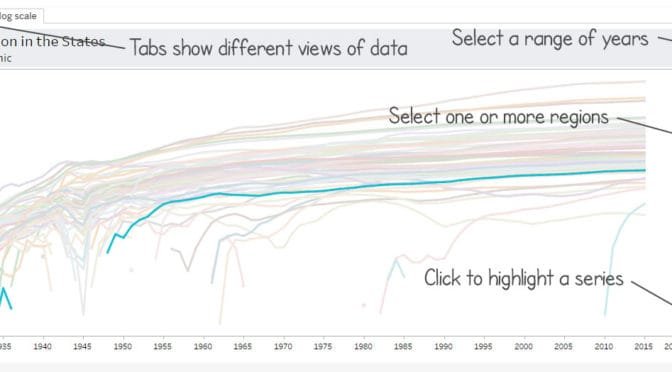

Populations of the states

An interactive table and charts of populations in the states and regions, starting in 1929.

-

Kansas government spending

Kansas government spending, starting in 1967. Total spending and per capita spending, adjusted for inflation. Also, spending as percent of Kansas GDP.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Lawrence Reed of Foundation for Economic Education

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV. Lawrence W. Reed, who is president of the Foundation for Economic Education.

-

Kansas and Arizona schools

Arizona shows that Kansas is missing out on an opportunity to provide better education at lower cost.

-

Public school experts

Do only those within the Kansas public schooling community have a say?