Tag: Wichita city government

-

Wichita sends educational mailer to non-Wichitans, using Wichita taxes

Why is the City of Wichita spending taxpayer money mailing to voters who don’t live in the city and can’t vote on the issue?

-

Tax your food, but not his

Does this seem fair and just, that the president of a restaurant chain would campaign for higher sales tax on groceries?

-

Tax not me, but food for the poor

This is Union Station in downtown Wichita. Its owner has secured a deal whereby future property taxes will be diverted to him rather than funding the costs of government like fixing streets, running the buses, and paying schoolteachers. This project may also receive a sales tax exemption. But as you can see, the owner wants…

-

Wichita sales tax hike harms low income families most severely

Analysis of household expenditure data shows that a proposed sales tax in Wichita affects low income families in greatest proportion, confirming the regressive nature of sales taxes.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: The proposed one cent per dollar Wichita sales tax

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: We’ll talk about the proposed Wichita sales tax, including who pays it, and who gets special exemptions from paying it. Then, can we believe the promises the city makes about accountability and transparency? Finally, has the chosen solution for a future water supply proven itself as viable, and why are…

-

By threatening an unwise alternative, Wichita campaigns for the sales tax

To pay for a new water supply, Wichita gives voters two choices and portrays one as exceptionally unwise. In creating this either-or fallacy, the city is effectively campaigning for the sales tax.

-

Should Wichita expand a water system that is still in commissioning stage?

In this script from the next episode of WichitaLiberty.TV, I report my concerns about rushing a decision to expand a water production system that has not yet proven itself.

-

For Wichita Chamber of Commerce chair, it’s sales tax for you, but not for me

A Wichita company CEO applied for a sales tax exemption. Now as chair of the Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce, he wants you to pay more sales tax, even on the food you buy in grocery stores.

-

Kansas sales tax on groceries is among the highest

Kansas has nearly the highest statewide sales tax rate for groceries. Cities and counties often add even more tax on food.

-

Old Town Cinema TIF update

The City of Wichita Department of Fiance has prepared an update on the financial performance of the Old Town Cinema Tax Increment Financing (TIF) District. There’s not much good news in this document.

-

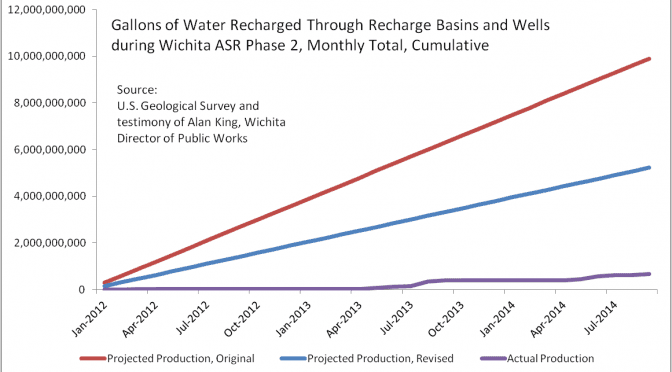

Wichita ASR water recharge project: The statistics

As Wichita voters consider spending $250 million expanding a water project, we should look at the project’s history. So far, the ASR program has not performed near expectations, even after revising goals downward.

-

Has the Wichita ASR water project been working?

Here is the cumulative production of the Wichita ASR project compared with projections. The city and the “Yes Wichita” campaign say the ASR project is proven and is working. Do you agree?