Category: Wichita city government

-

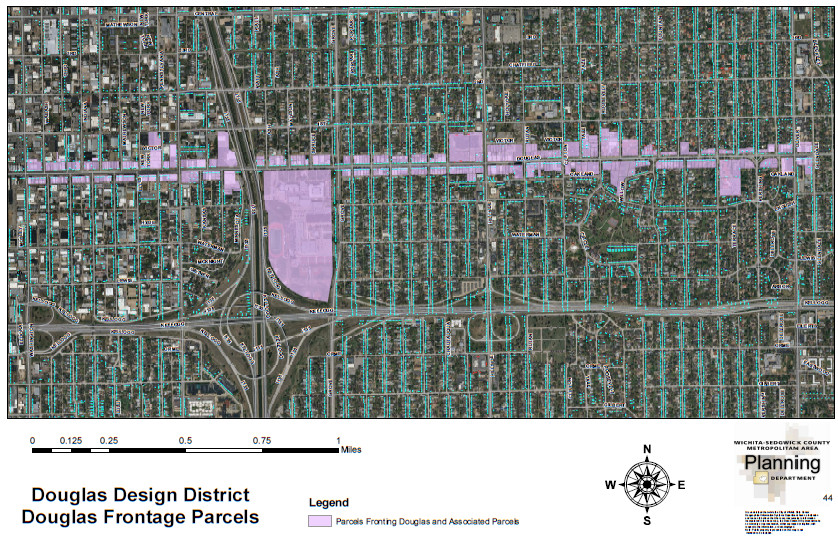

Business improvement district on tap in Wichita

The Douglas Design District seeks to transform from a voluntary business organization to a tax-funded branch of government.

-

It may become more expensive in Wichita

The City of Wichita plans to create a large district where extra sales tax will be charged.

-

Downtown Wichita population is up

New Census Bureau data shows the population growing in downtown Wichita.

-

Wichita water plant contract

Wichita should consider discarding the water plant contract in order to salvage its reputation and respect for process.

-

The Wichita baseball team’s name

Is the name of the new Wichita baseball team important? Yes, as it provides insight.

-

Wichita consent agenda reform proposed

The Wichita city council will consider reforms to the consent agenda.

-

City comeback bingo

Wichita has amenities that are promoted as creating an uncommonly superior quality of life here, but many are commonplace across the country.

-

From Pachyderm: Save Century II

From the Wichita Pachyderm Club: Speakers promoting the saving of the Century II Convention and Performing Arts Center in downtown Wichita.

-

Longwell: ‘There is no corruption’

Wichita Mayor Jeff Longwell says there is no corruption involving him, but this is only because of loose and sloppy Kansas and Wichita laws.

-

Questions for Mayor Jeff Longwell

Wichita Mayor Jeff Longwell urges Wichitans to reach out to him with questions through email and social media.

-

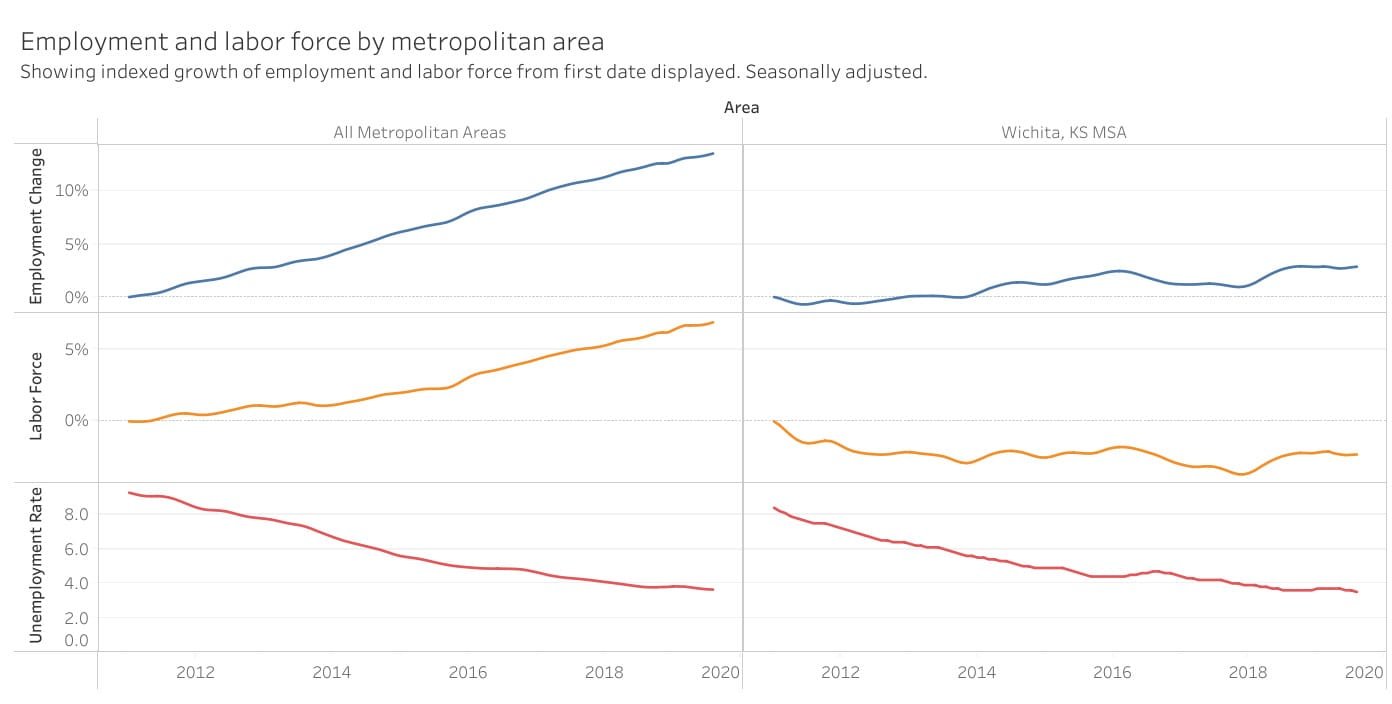

The cause of the low unemployment rate in Wichita

The unemployment rate for Wichita and the nation is nearly equal over the last eight years. Job growth for Wichita, however, has been much slower than the nation, and the labor force for Wichita is actually smaller than in January 2011. This is what has led to a low unemployment rate in Wichita: Slow job…

-

Wichita jobs and momentum

Given recent data and the CEDBR forecasts, Wichita’s momentum is a slowly growing economy, with the rate of growth declining.