Tag: Economic development

-

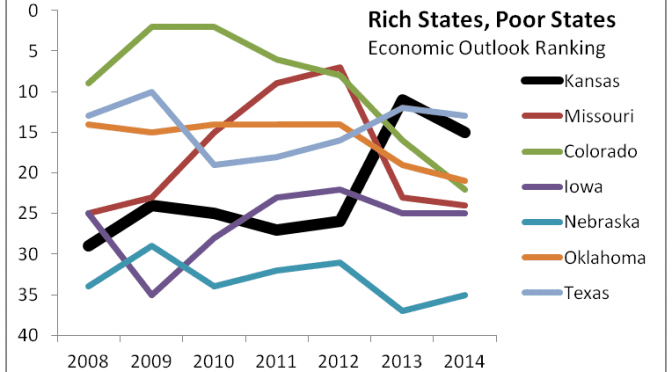

Rich States, Poor States for 2014 released

In the 2014 edition of Rich States, Poor States, Kansas continues with middle-of-the-pack performance rankings, and fell in the forward-looking forecast.

-

Wichita not good for small business

When it comes to having good conditions to support small businesses, well, Wichita isn’t exactly at the top of the list, according to a new ranking from The Business Journals.

-

Wichita City Council fails to support informing the taxed

What does it say about Wichita’s economic development strategy that if you fully inform citizens and visitors, it renders a tool useless?

-

In Wichita, if you don’t like it, just don’t go there

As Wichita city officials prepare a campaign to raise the sales tax in Wichita, let’s recall some council members’ attitude towards citizens.

-

State employment visualizations

There’s been dueling claims and controversy over employment figures in Kansas and our state’s performance relative to others. I present the actual data in interactive visualizations that you can use to make up your own mind.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Wichita’s city tourism fee, Special taxes for special people

The Wichita City Council will hold a meeting regarding an industry that wants to tax itself, but really is taxing its customers. Also, the city may be skirting the law in holding the meeting. Then: The Kansas Legislature is considering special tax treatment for a certain class of business firms. What is the harm in…

-

As landlord, Wichita has a few issues

Commercial retail space owned by the City of Wichita in a desirable downtown location was built to be rented. But most is vacant, and maintenance issues go unresolved.

-

Wichita planning documents hold sobering numbers

Planning documents released this week hold information that ought to make Wichitans think, and think hard. The amounts of money involved are large, and portions represent deferred maintenance. That is, the city has not been taking care of the assets that taxpayers have paid for.

-

Wichita’s legislative agenda favors government, not citizens

Wichita’s legislative agenda contains many items contrary to economic freedom, capitalism, limited government, and individual liberty. Yet, Wichitans pay taxes to have this agenda promoted.

-

Kansas Open Records Act and the ‘public agency’ definition

Despite the City of Wichita’s support for government transparency, citizens have to ask the legislature to add new law forcing the city and its agencies to comply with the Kansas Open Records Act.

-

Economic development in Wichita, steps one and two

Critics of the economic development policies in use by the City of Wichita are often portrayed as not being able to see and appreciate the good things these policies are producing, even though they are unfolding right before our very eyes. The difference is that some look beyond the immediate — what is seen –…

-

Viewing the seen and unseen

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.