Tag: Economic freedom

-

Year in Review: 2014

Here is a sampling of stories from Voice for Liberty in 2014.

-

Myth: Markets promote greed and selfishness

Markets make it possible for the most altruistic, as well as the most selfish, to advance their purposes in peace, writes Tom G. Palmer.

-

Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce: What is the attitude towards taxes?

Does the Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce support free markets, capitalism, and economic freedom, or something else?

-

KU records request seen as political attack

A request for correspondence belonging to a Kansas University faculty member is a blatant attempt to squelch academic freedom and free speech.

-

Foundations of a Free Society

Freedom creates prosperity. It unleashes human talent, invention and innovation, creating wealth where none existed before, writes Eamonn Butler of the Adam Smith Institute.

-

Thumbs up for Americans for Prosperity

On the television news program Journal Editorial Report, Potomac Watch columnist for The Wall Street Journal editorial page Kimberley A. Strassel gave a thumbs up to Americans for Prosperity for its work in the recent election.

-

Richard Ranzau, slayer of cronyism

In Sedgwick County, an unlikely hero emerges in the battle for capitalism over cronyism.

-

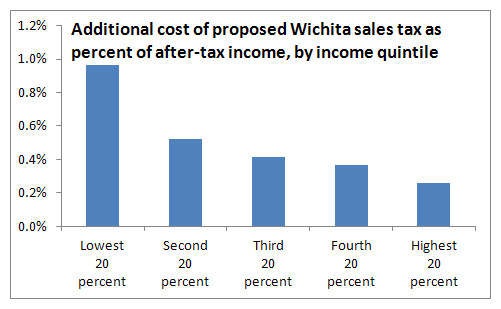

Wichita sales tax hike harms low income families most severely

Analysis of household expenditure data shows that a proposed sales tax in Wichita affects low income families in greatest proportion, confirming the regressive nature of sales taxes.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Author and philosopher Andrew Bernstein

Andrew Bernstein is a proponent of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, an author, and a professor of philosophy. We talk about capitalism and other subjects.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Arrival of Uber a pivotal moment for Wichita

Now that Uber has started service in Wichita, the city faces a decision. Will Wichita move into the future by embracing Uber, or remain stuck in the past?

-

Wichita sales tax hike would hit low income families hardest

Analysis of household expenditure data shows that a proposed sales tax in Wichita affects low income families in greatest proportion, confirming the regressive nature of sales taxes.

-

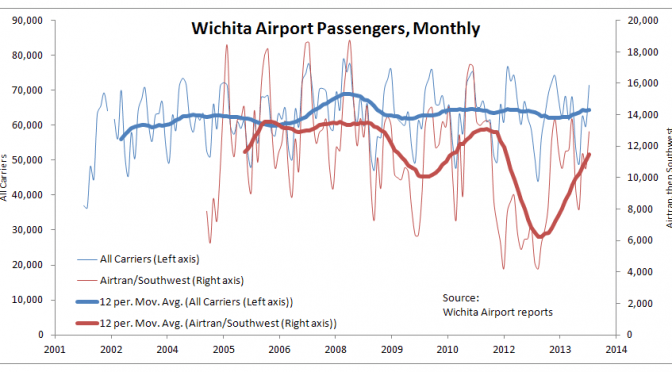

Wichita airport statistics updated

Why do Kansans pay taxes, including sales tax on food, to fund millions in subsidy to a company that is experiencing a sustained streak of record profits?