From February 2014.

“The purpose of high taxes on the rich is not to get the rich to pay money, it’s to get the middle class to feel better about paying high taxes.”

This is what Jim Pinkerton, the journalist, Fox News contributor, and co-founder of the RATE (Reforming America’s Taxes Equitably) Coalition told an audience at a conference titled “The Tax & Regulatory Impact on Industry, Jobs & The Economy, and Consumers” produced by the Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity.

This is what Jim Pinkerton, the journalist, Fox News contributor, and co-founder of the RATE (Reforming America’s Taxes Equitably) Coalition told an audience at a conference titled “The Tax & Regulatory Impact on Industry, Jobs & The Economy, and Consumers” produced by the Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity.

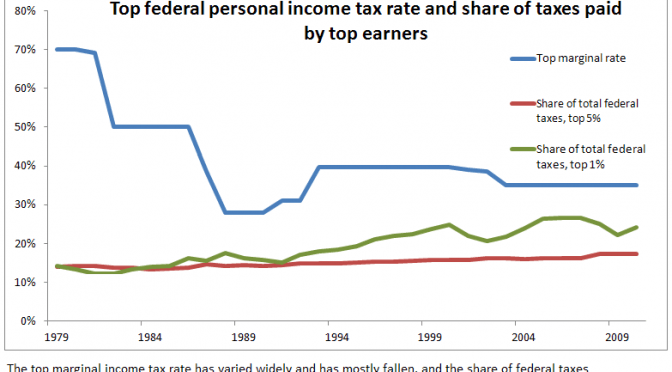

Pinkerton was referring to the economist F.A. Hayek. Others have also noted that changes to marginal tax rates often have little impact on the amount of taxes actually paid. The top marginal tax rate — that’s the rate that applies to high income earners on most of their income — was above 90 percent during most of the 1950s. From 2003 to 2012 it was 35 percent, and is now 39.6 percent.

The top marginal tax rate is the rate that applies to income. It’s not the same as what is actually paid. This fact is unknown or ignored by those who clamor for higher taxes on the rich. They often cite the rising prosperity of the 1950s as caused by the high marginal tax rate in effect at the time.

The mistake the progressives make is equating tax rates with the tax actually paid. For many people, there is a direct relationship. For workers who earn a paycheck, there’s not much they can do to change the timing of their income, find tax shelters, or shift income to capital gains. When income tax rates rise, they have to pay more. But rich people can use these and other strategies to reduce the taxes they pay.

But as Pinkerton told the conference attendees, the high tax rates make the middle class feel better about paying their own taxes. They may take comfort in the fact that someone else is worse off, at least based on the misconception that high tax rates mean rich people actually pay correspondingly higher tax.

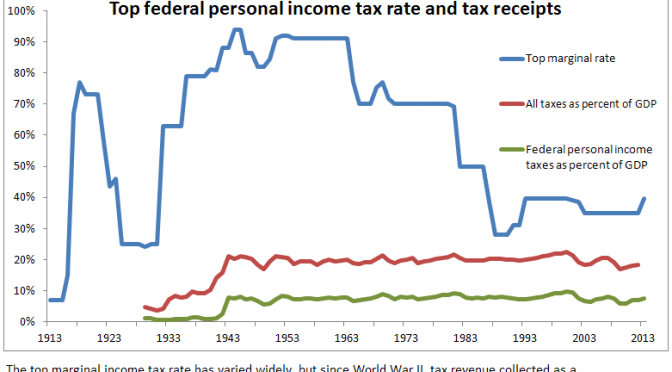

In 2010 W. Kurt Hauser explained in The Wall Street Journal: “Even amoebas learn by trial and error, but some economists and politicians do not. The Obama administration’s budget projections claim that raising taxes on the top 2% of taxpayers, those individuals earning more than $200,000 and couples earning $250,000 or more, will increase revenues to the U.S. Treasury. The empirical evidence suggests otherwise. None of the personal income tax or capital gains tax increases enacted in the post-World War II period has raised the projected tax revenues. Over the past six decades, tax revenues as a percentage of GDP have averaged just under 19% regardless of the top marginal personal income tax rate. The top marginal rate has been as high as 92% (1952-53) and as low as 28% (1988-90). This observation was first reported in an op-ed I wrote for this newspaper in March 1993. A wit later dubbed this ‘Hauser’s Law.’”

Incentives matter, economists tell us. People react to changes in tax law. As tax rates rise, people seek to reduce their taxable income. A common strategy is to make investments in economically unproductive tax shelters. There is less incentive to work, to save and build up capital stocks, and invest. These are some of the reasons why tax rate hikes usually don’t generate the promised revenue.

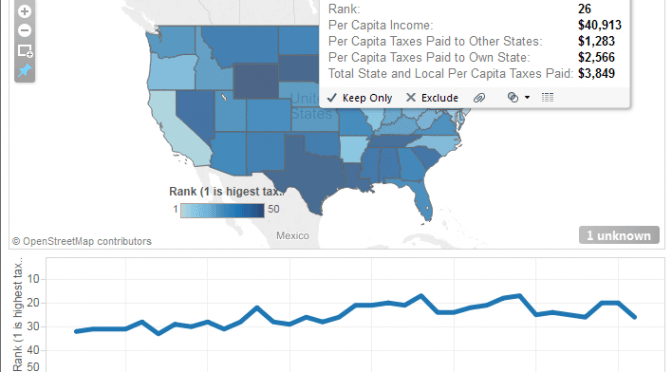

The subtitle to Hauser’s article is “Tax revenues as a share of GDP have averaged just under 19%, whether tax rates are cut or raised. Better to cut rates and get 19% of a larger pie.” The nearby chart illustrates. The top line, the top marginal tax rate in effect for year year, varies widely. The other two lines show total taxes and federal income taxes as a percent of gross domestic product. Since World War II, these lines are fairly constant, even as the top marginal tax rate varies.

Data is from Bureau of Economic Analysis (part of the U.S. Department of Commerce) along with my calculations.

“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.” — Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman

“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.” — Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman