Tag: Economic development

-

Downtown Wichita population

Wichita economic development officials use a convoluted method of estimating the population of downtown Wichita, producing a number much higher than Census Bureau estimates.

-

Wichita metro employment by industry

An interactive visualization of Wichita-area employment by industry.

-

Downtown Wichita jobs decline

Despite heavy promotion and investment in downtown Wichita, the number of jobs continues to decline.

-

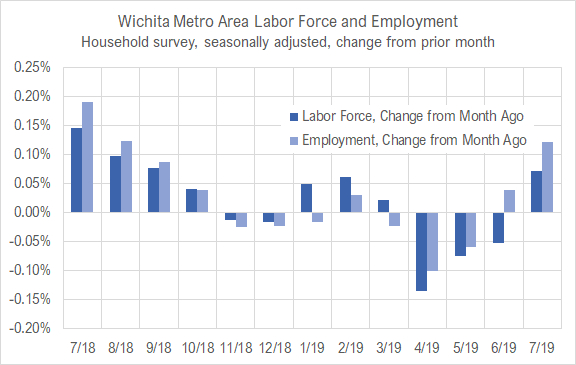

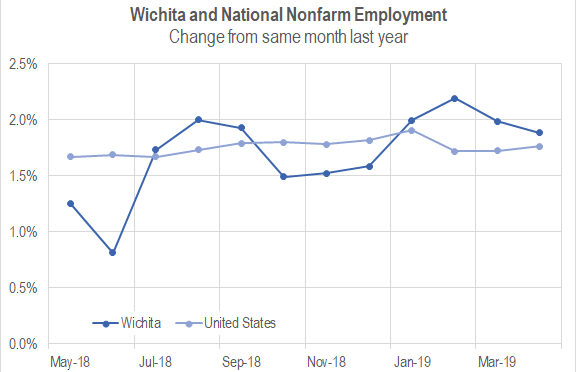

Wichita jobs and employment, July 2019

For the Wichita metropolitan area in July 2019, the labor force is up, the number of unemployed persons is down, the unemployment rate is down, and the number of people working is up when compared to the same month one year ago. Seasonal data shows small increases in labor force and jobs from June.

-

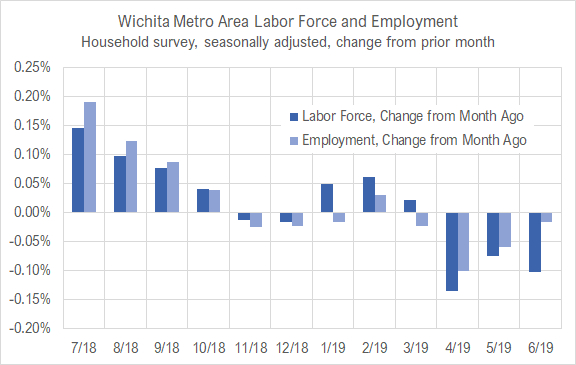

Wichita jobs and employment, June 2019

For the Wichita metropolitan area in May 2019, the labor force is up, the number of unemployed persons is up, the unemployment rate is unchanged, and the number of people working is up when compared to the same month one year ago. Seasonal data shows declines in labor force and jobs from April.

-

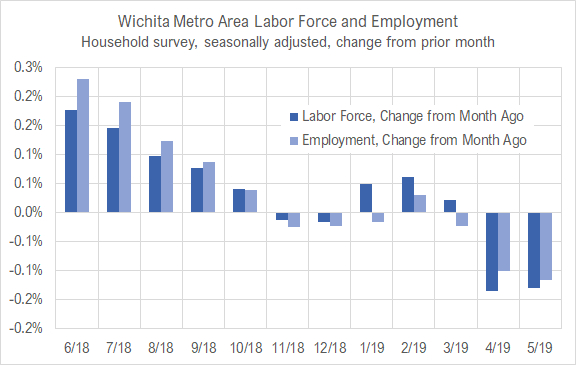

Wichita jobs and employment, May 2019

For the Wichita metropolitan area in May 2019, the labor force is up, the number of unemployed persons is up, the unemployment rate is unchanged, and the number of people working is up when compared to the same month one year ago. Seasonal data shows declines in labor force and jobs from April.

-

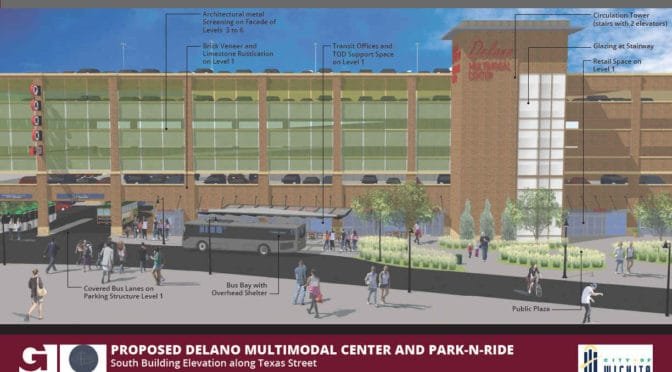

The Wichita transit center application

The City of Wichita has made an application to the federal government for funding for a new transit center.

-

Wichita population, according to Mayor Longwell

It is unfortunate that Wichita city and metro populations are falling. It is unimaginable that our city’s top leader is not aware of the latest population trends.

-

Wichita and other airports

How does the Wichita airport compare to others?

-

New metropolitan rankings regarding knowledge-based industries and entrepreneurship

New research provides insight into the Wichita metropolitan area economy and dynamism.

-

Wichita airport traffic

Traffic is rising at the Wichita airport. How does it compare to others?

-

Wichita jobs and employment, April 2019

For the Wichita metropolitan area in April 2019, the labor force is up, the number of unemployed persons is down, the unemployment rate is down, and the number of people working is up when compared to the same month one year ago. Seasonal data shows small declines in labor force and jobs from March.