Tag: Economics

-

In Kansas and Wichita, there’s a reason for slow growth

If we in Kansas and Wichita wonder why our economic growth is slow and our economic development programs don’t seem to be producing results, there is data to tell us why: Our tax rates are too high.

-

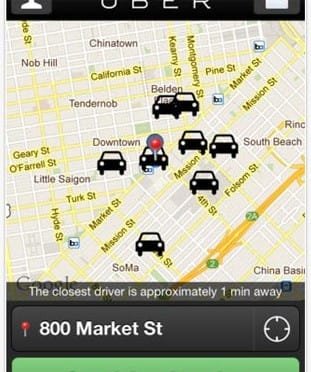

Uber, not for Wichita

A novel transportation service worked well for me on a recent trip to Washington, but Wichita doesn’t seem ready to embrace such innovation.

-

Intrust Bank Arena: Not accounted for like a business

Proper attention given to the depreciation expense of Intrust Bank Arena in downtown Wichita recognizes and accounts for the sacrifices of the people of Sedgwick County and its visitors to pay for the arena. It’s a business-like way of accounting, but a well-hidden secret.

-

Kauffman index of entrepreneurial activity

The performance of Kansas in entrepreneurial activity is not high, compared to other states.

-

Kansas economy has been lagging for some time

Critics of tax reform in Kansas point to recent substandard performance of the state’s economy. The recent trend, however, is much the same as the past.

-

In Wichita, capitalism doesn’t work, until it works

Attitudes of Wichita government leaders towards capitalism reveal a lack of understanding. Is only a government-owned hotel able to make capital improvements?

-

Debunking CBPP on tax reform and school funding — Part 4

States that spend less, tax less — and grow more, writes Dave Trabert of Kansas Policy Institute.

-

Myth: The Kansas tax cuts haven’t boosted its economy

While tax reform hasn’t produced the “shot of adrenaline” predicted by Governor Brownback, the problem is one of political enthusiasm rather than economics, writes Dave Trabert of Kansas Policy Institute.

-

Renewables portfolio standard bad for Kansas economy, people

A report submitted to the Kansas Legislature claims the Kansas economy benefits from the state’s Renewables Portfolio Standard, but an economist presented testimony rebutting the key points in the report.

-

Kauffman paper on local business incentive programs

The paper “Evaluating Firm-Specific Location Incentives: An Application to the Kansas PEAK Program,” from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation introduces a proposed evaluation method and applies it to Promoting Employment Across Kansas (PEAK), one of that state’s primary incentive programs.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Kansas school finance and reform, Charles Koch on why he fights for liberty

The Kansas legislature passed a school finance bill that contains reform measures that the education establishment doesn’t want. In response, our state’s newspapers uniformly support the system rather than Kansas schoolchildren. Then, in the Wall Street Journal Charles Koch explains why liberty is important, and why he’s fighting for that.