Tag: Greater Wichita Partnership

-

Wichita population, according to Mayor Longwell

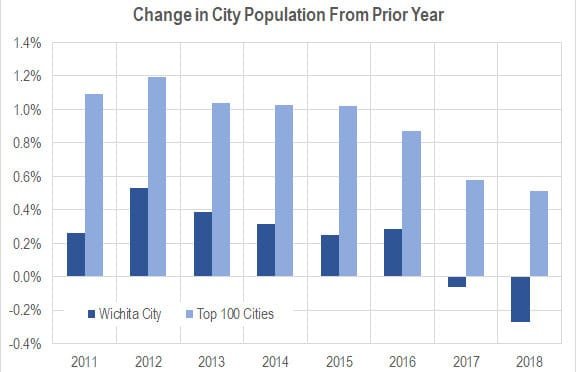

It is unfortunate that Wichita city and metro populations are falling. It is unimaginable that our city’s top leader is not aware of the latest population trends.

-

Wichita and other airports

How does the Wichita airport compare to others?

-

New metropolitan rankings regarding knowledge-based industries and entrepreneurship

New research provides insight into the Wichita metropolitan area economy and dynamism.

-

Wichita airport traffic

Traffic is rising at the Wichita airport. How does it compare to others?

-

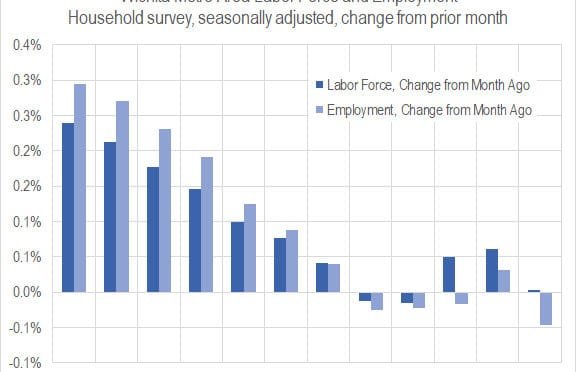

Wichita jobs and employment, April 2019

For the Wichita metropolitan area in April 2019, the labor force is up, the number of unemployed persons is down, the unemployment rate is down, and the number of people working is up when compared to the same month one year ago. Seasonal data shows small declines in labor force and jobs from March.

-

Wichita population, 2018

The City of Wichita lost 1,052 in population from 2017 to 2018, a decline of 0.27 percent.

-

Sedgwick County job growth continues strong pace

In the fourth quarter of 2018, Sedgwick County continued strong job growth.

-

Wichita personal income growing, but slowly

Among the nation’s 383 metropolitan areas, Wichita ranked 347th for personal income growth.

-

More Wichita planning on tap

We should be wary of government planning in general. But when those who have been managing and planning the foundering Wichita-area economy want to step up their management of resources, we risk compounding our problems.

-

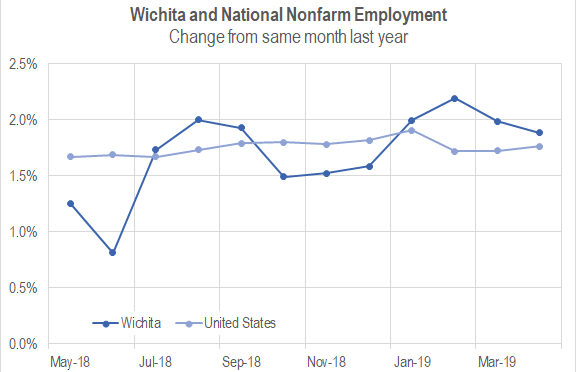

State of the City, Wichita: Employment strength

Wichita Mayor Jeff Longwell’s State of the City video relies on flimsy evidence and plucks scant good news from a sea of bad. This is a problem.

-

Wichita jobs and employment, March 2019

For the Wichita metropolitan area in March 2019, jobs are up, the labor force is up, and the unemployment rate is unchanged when compared to the same month one year ago. Seasonal data shows a small decline in jobs from February.

-

State of the City, Wichita: The bright future

Wichita Mayor Jeff Longwell’s State of the City video doesn’t seem to be based on reality.