Tag: Wichita city government

-

Wichita’s WaterWalk apartment deal

Wichita is ready to consider another giveaway to politically-connected interests at the expense of citizens and taxpayers.

-

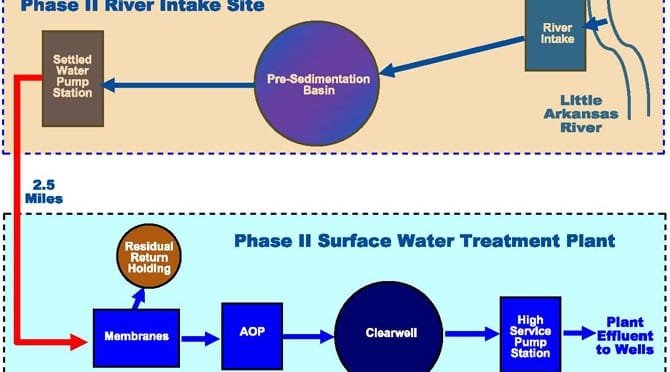

Wichita water statistics update

The Wichita ASR water project produced little water in July, continuing to fail to produce water at the projected rate or design capacity.

-

In Wichita, an incomplete economic development analysis

The Wichita City Council will consider an economic development incentive based on an analysis that is nowhere near complete.

-

Cash incentives in Wichita

Wichita city leaders are proud to announce the end of cash incentives, but they were only a small portion of the total cost of incentives.

-

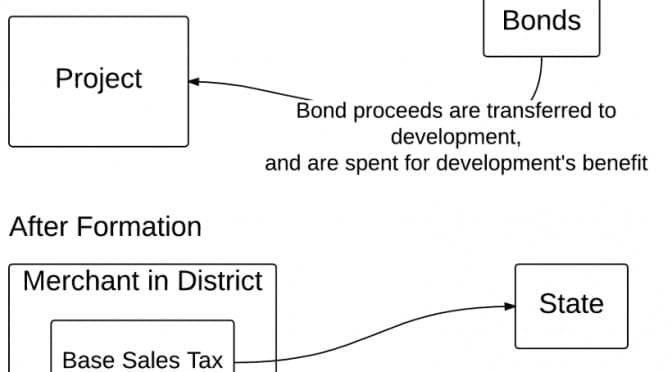

In Wichita, benefitting from your sales taxes, but not paying their own

A Wichita real estate development benefits from the sales taxes you pay, but doesn’t want to pay themselves.

-

Westar: First, control blatant waste

As our electric utility asks for a rate increase, let’s first ask that it stop blatant waste.

-

Wichita airport spends $180K on ads

The Wichita airport spends to produce and broadcast a television advertisement, and taxpayers didn’t have to pay. Sort of.

-

WichitaLiberty.TV: Bad news from Topeka on taxes and schools, and also in Wichita. Also, a series of videos that reveal the nature of government.

In this episode of WichitaLiberty.TV: The sales tax increase is harmful and not necessary. Kansas school standards are again found to be weak. The ASR water project is not meeting expectations. Then, the Independent Institute has produced a series of videos that illustrate the nature of government. Episode 88, broadcast July 19, 2015.

-

In Wichita, wasting electricity a chronic problem

The chronic waste of electricity in downtown Wichita is a problem that probably won’t be solved soon, given the city’s attitude.

-

Wichita water statistics update

The Wichita ASR water project had a relatively good month in June, but has not been producing water at the projected rate or design capacity.

-

Airport statistics

Updated charts of flights and passengers for Wichita and the U.S.

-

Wichita property taxes still high, but comparatively better

An ongoing study reveals that generally, property taxes on commercial and industrial property in Wichita are high. In particular, taxes on commercial property in Wichita are among the highest in the nation, although Wichita has improved comparatively.